28 June 1919: the Treaty of Versailles

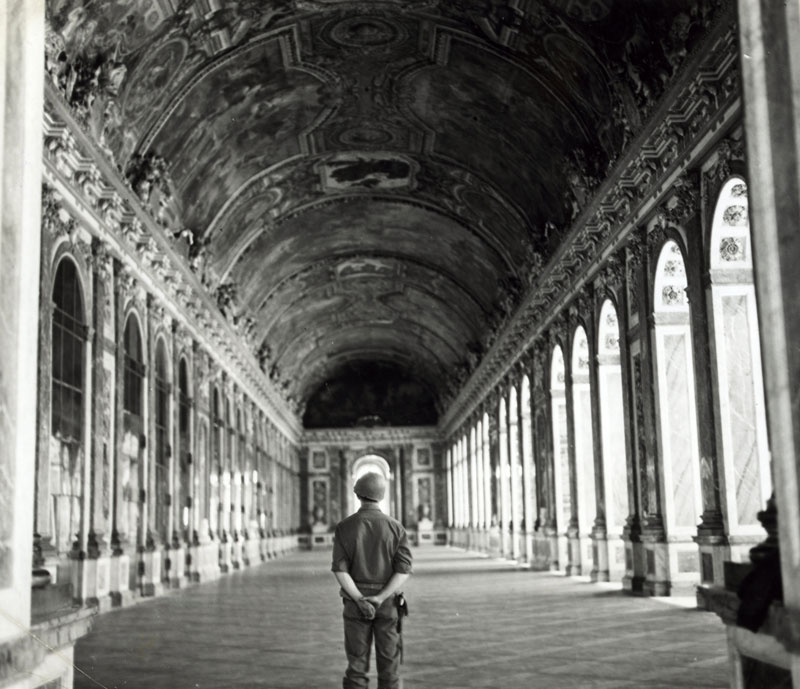

Signed on the anniversary of the assassination in Sarajevo which triggered the First World War, the Treaty of Versailles formally put an end to the war and set out the sanctions and reparations to be borne by Germany. The choice of location was also symbolic: the treaty was signed in the Hall of Mirrors which also witnessed the proclamation of the German Empire in 1871.

Since 1871, the Hall of Mirrors had been a flashpoint of Franco-German tension. In the early 20th century Versailles became a fully-fledged tourist destination, popular with international visitors. The renaissance of the royal estate, overseen by head curator Pierre de Nolhac, included restoration work made possible by donations from John D. Rockefeller in 1924 and 1927.

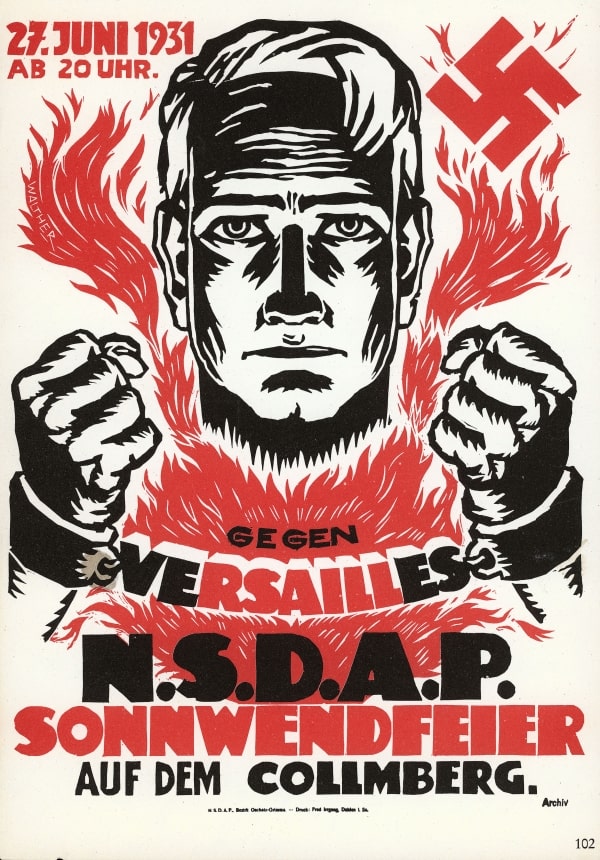

30 January 1933: Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Weimar Republic

In the 1930s, many countries across Europe witnessed a resurgence of nationalist movements. In Germany, the Nazi part swept to power. Its leader, Adolf Hitler, denounced the Treaty of Versailles as a form of enslavement of the German people.

France, like many other European nations, began discreetly preparing for another war. The country’s museums gradually rolled out a programme of “passive defence” measures designed to protect the national collections.

1933: the Ministry for Fine Arts asked all museums in the Greater Paris region to draw up a list of works earmarked for evacuation in the event of a conflict.

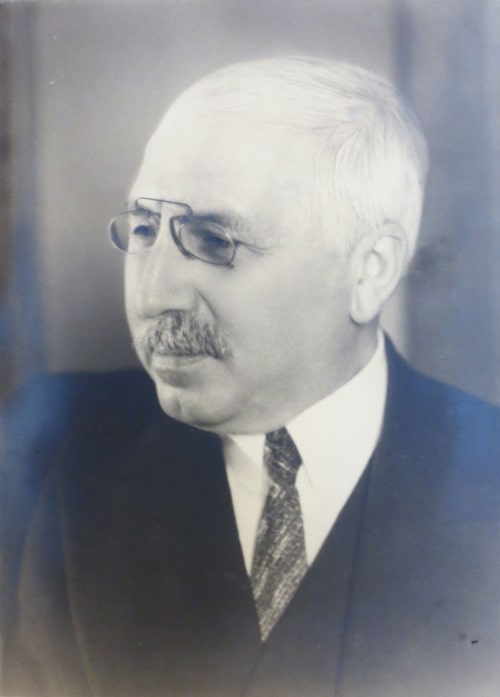

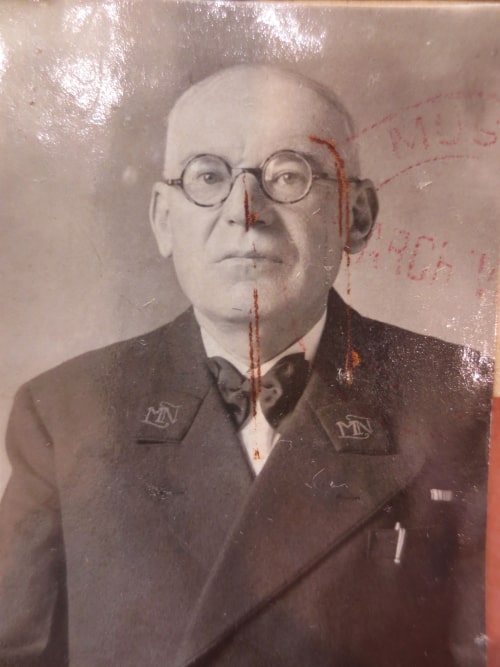

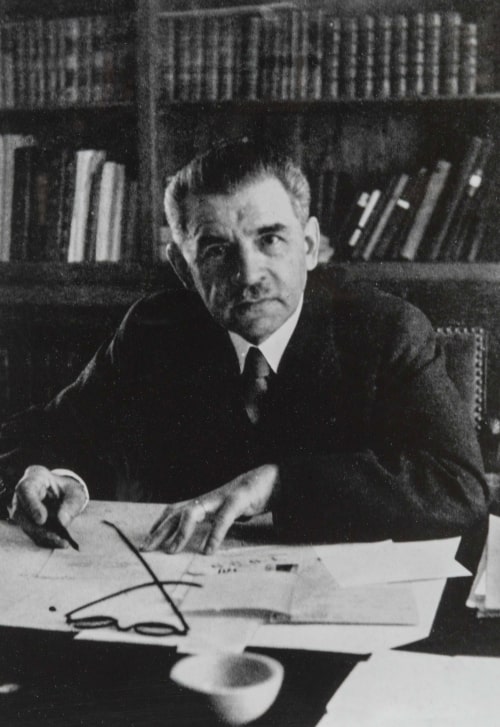

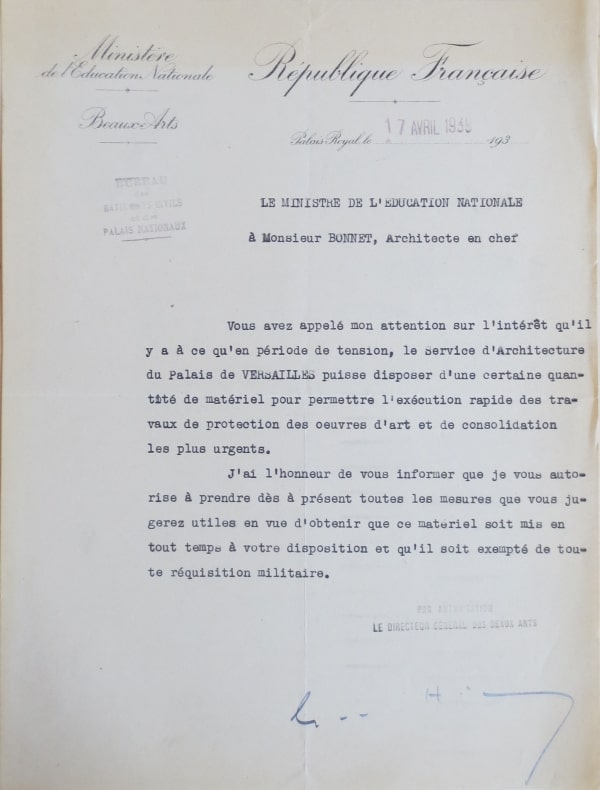

This operation was overseen by Jacques Jaujard, Deputy Director for National Museums. At Versailles, Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré began work on a protective strategy. In September 1933 he submitted a twenty-page report to Jacques Jaujard. In 1935, architect in chief Patrice Bonnet submitted his own conclusions to the Directorate for Fine Arts.

By the mid-1930s, war looked increasingly inevitable. At Versailles, Patrice Bonnet raised the alarm about the lack of human resources available in the event of a general mobilisation, and the risks that the palace could be attacked from the air. Bonnet was concerned that the estate’s proximity to numerous military targets, including the Satory camp, left it vulnerable to enemy bombing. The architect was also at pains to remind his superiors of the symbolic value of the palace in the eyes of the German authorities. In his report, he also recommended the construction of an underground shelter for the staff (with room for around 60 people) beneath the Royal Courtyard.

Meanwhile, Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré was liaising with the Museums Directorate regarding the protective measures to be taken if war should break out.

“ Dear Sir, In the summer of 1933 you requested a report on the evacuation of the museum at Versailles, which I presented to you directly in September of that year (…) In light of the present circumstances, we would like to know more about the current state of affairs, and the actions you propose to take (…) we need directives, or even precise orders, on what is to be done if the need arises. ”

Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré to Jacques Jaujard, 13 March 1936

By the summer of 1936, the National Museums Directorate was scouting out buildings which could be used to shelter artworks evacuated from the country’s museums. Many possibilities were discussed – including the Château de Chambord – but the need to maintain confidentiality was paramount.

With Paris hosting an International Exposition from 25 May to 25 November 1937, the number of visitors to the Palace of Versailles exceeded one million for the first time.

21 July 1938: state visit to Versailles by the British King and Queen.

In these troubled political times, the King and Queen made an official visit to France and stopped off at Versailles in July 1938. To mark the occasion, King George VI and Queen Consort Elizabeth were guests of honour at a dinner hosted by President Albert Lebrun in the Hall of Mirrors.

July 1938: Gaston Brière retired from his post as head curator of the National Museum of Versailles.

His replacement was Pierre Ladoué, formerly deputy curator of the Musée du Luxembourg.

The Sudeten Crisis

In the late summer of 1938, the Sudeten Crisis raised fears that another war was imminent. France’s museums hurriedly launched into their evacuation procedures: the Louvre dispatched Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa to the Château de Chambord. At Versailles, an order was placed in September for 20,000 extra sandbags, intended to protect the building. Museums were told to prepare to close their doors to the public, if the conflict should intensify.

24 September 1938: anti-aircraft guns installed on the roof of the palace

30 September 1938: signature of the Munich Agreement

Signed on 30 September 1938, the Munich Agreement brought the Sudeten Crisis to an end. War had been averted, and it was time to take stock of recent events. The experience had been a chastening one for the Palace of Versailles: not a single artwork had left the estate, due to a lack of equipment and manpower. These difficulties obliged Pierre Ladoué and Patrice Bonnet to review their respective strategies. Substantial differences of opinion emerged between the two men, with the curator accusing the architect in chief of failing to make sufficient preparations for sheltering both the staff and the collections. Patrice Bonnet, meanwhile, was incensed that machine guns had been installed on the roof of the palace…

“ It’s almost as if they were deliberately providing a pretext for destroying the Palace of Versailles. We would be given short shrift by the international organisations, if it emerge that we had been using the rooftops of Versailles as machine gun nests before war had even been declared. ”

Patrice Bonnet’s report to the Director General for Fine Arts, Versailles, 2 December 1938. Médiathèque de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine

In early 1939, the National Museums Directorate approved Patrice Bonnet’s plans for an underground bomb shelter. They gave him the green light to create a concrete-lined bunker running beneath the equestrian statue of Louis XIV, cutting across the Honour Courtyard from north to south.

The National Museums Directorate had by now resumed its work scouting out available châteaux elsewhere in France, which could be used to store evacuated artworks in the event of an armed conflict.

5 April 1939: Albert Lebrun is re-elected President of the French Republic

5 May 1939: inauguration of the exhibition « Versailles in 1789 »

Spring 1939 saw the official opening of the exhibition « Versailles in 1789 », marking the 150th anniversary of the French Revolution. President Albert Lebrun, fresh from his election victory, oversaw the official inauguration ceremony. The Royal Tennis Court was reorganised for the occasion, and the apartments of Madame de Maintenon – which housed the exhibition – were entirely repainted.

Inauguration of the exhibition ‘Versailles in 1789’ by Albert Lebrun © Palace of Versailles, Dist. RMN / © Christophe Fouin

Letter from the Directorate General for Fine Arts to Patrice Bonnet, 17 April 1939 © Archives of the Palace of Versailles / © Christophe Fouin

20-21 May 1939: first test runs of blackout procedures in the town of Versailles

5 August 1939: a new report on “Measures taken by the national museums in order to safeguard the national collections in the event of a war” was submitted to the Minister.

Less than a year after the Sudeten Crisis, France’s museums were now much better-prepared. Each institution was issued with the materials necessary to wrap and protect its collections, along with voluminous official instructions covering those works which would remain in situ and those which were to be transferred to depots.

France’s national museums, including Versailles, close their doors to the public

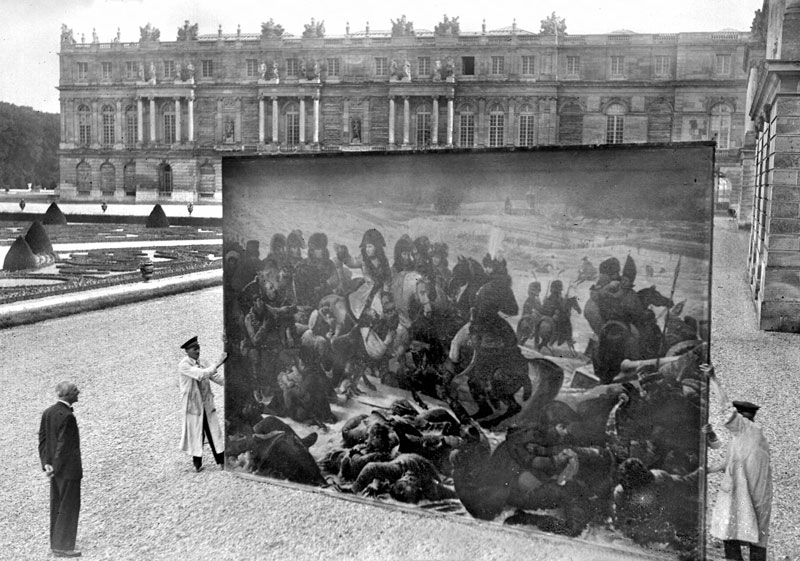

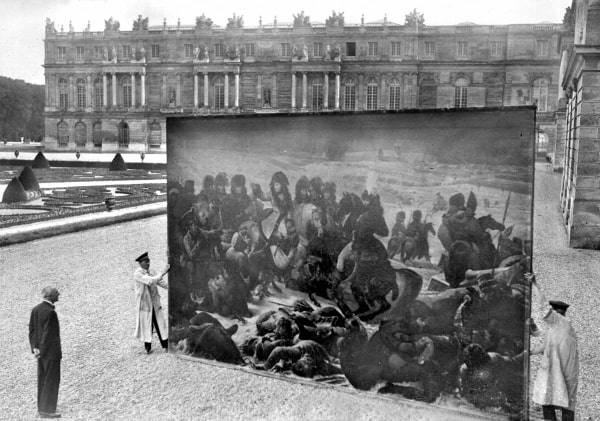

In late August 1939, the country’s museums closed to the public and began packing up their collections for evacuation to the designated depots. On 28 August, the Louvre sent the Mona Lisa to the Château de Chambord. On 29 August, the Palace of Versailles dispatched a first convoy of trucks containing artworks from its collections, headed for the Château de Brissac and the Château de Chambord.

“ On 29 August [1939], seven removal vehicles set off for Chambord. Four more left on 2 September. Two trucks headed for Brissac on 7 October. In total, they took with them 494 paintings, of which 283 were packed in cases, along with 32 tapestries and carpets, 52 wall hangings, 85 artworks, 32 pieces of furniture, including monumental clocks by Passement-Caffieri and Morand, as well as large and particularly precious items such as the desk of Louis XVI and the jewellery chest that belonged to Marie-Antoinette […] ”

Pierre Ladoué, head curator of the Palace of Versailles, And Versailles Was Saved, 1960

Nonetheless, a certain number of artworks did remain at the palace. Many were stored in the Orangery.

1st September 1939: France declared a general mobilisation of all available forces.

The national mobilisation depleted the palace staff. Only those considered invalid for military service, many of whom were veterans of the First World War, remained at Versailles alongside Pierre Ladoué, Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré and Patrice Bonnet.

France and Great Britain declare war on Germany

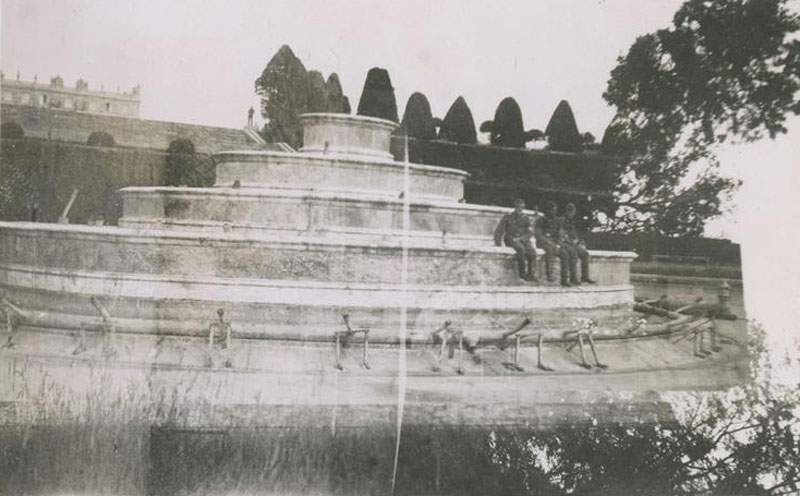

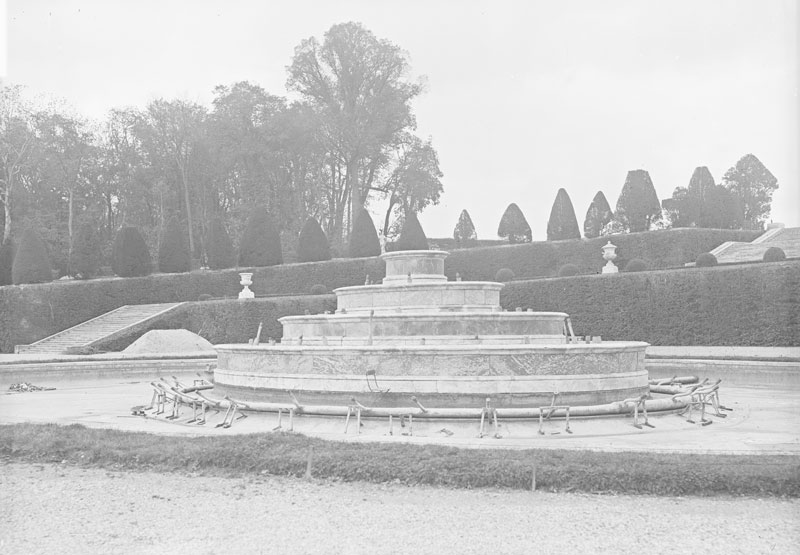

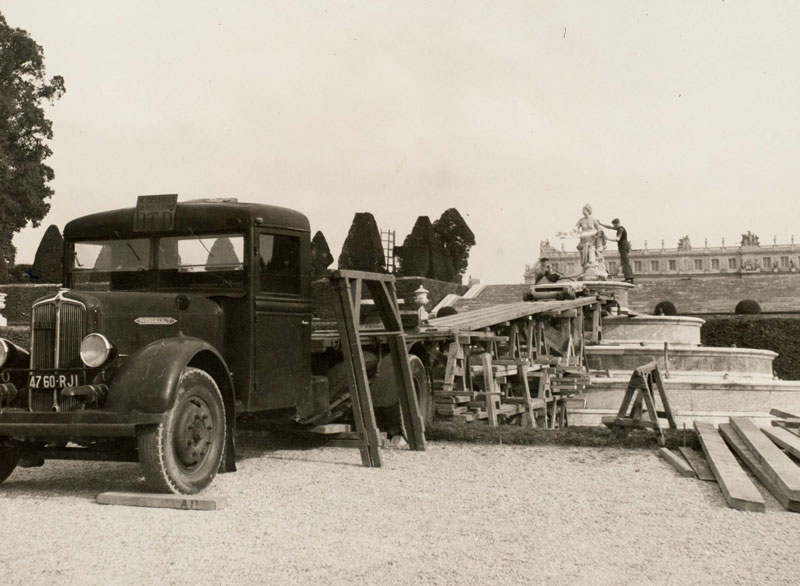

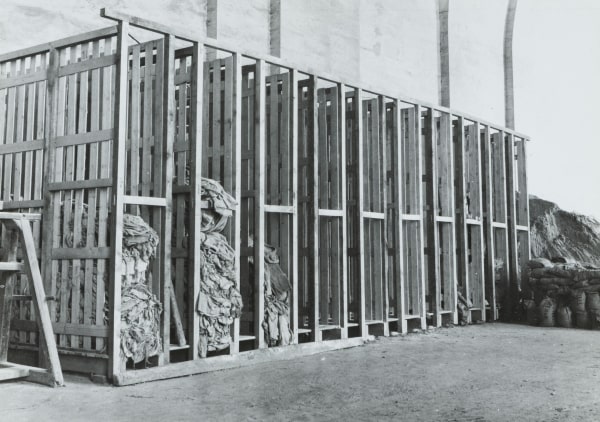

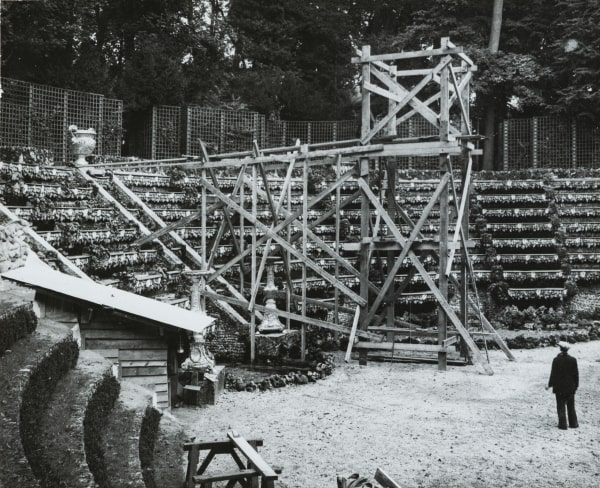

As soon as war was declared, Patrice Bonnet deployed his passive defence strategy. In September the gardens were closed to the public and all of the artworks usually displayed outdoors (statues, vases, the gilded ironwork of the Ballroom Grove etc.) were transferred to the Orangery for safekeeping, or else evacuated to the Abbaye des Vaux-de-Cernay, along with the statue from the Latona Fountain.

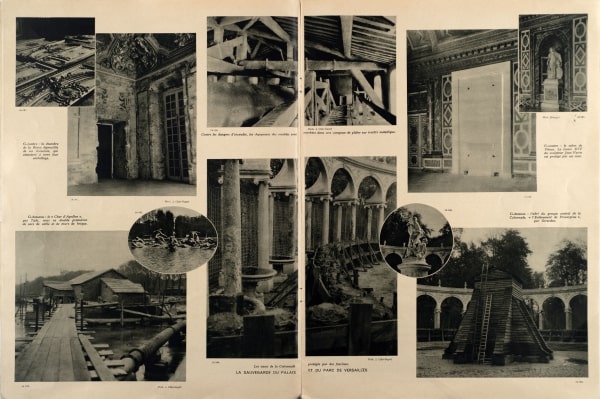

“Passive defence” in action in the Ballroom Grove, Autumn 1939 © Archives of the Palace of Versailles

“Passive defence” in action in the gardens of the Palace of Versailles, Autumn 1939 © Archives of the Palace of Versailles

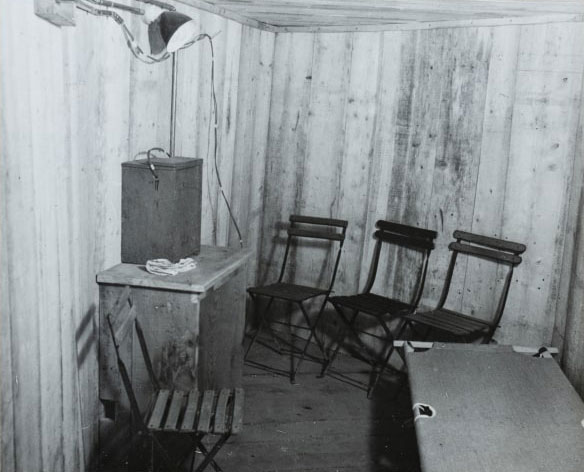

September 1939: shelters constructed for the palace staff.

Having failed in his bid to build a shelter underneath the Marble Courtyard, architect Patrice Bonnet instead constructed a shelter, an “earthbag blockhaus” on the garden terrace. A second shelter was installed beneath the vaulted Ballroom Grove, with space for 300 people. At the end of the month another shelter was constructed in the Apollo Grove, behind the sculpted fountains.

4 October 1939: the Grand Canal is drained

The Ministry for War had issued orders to camouflage the palace’s major water features, which could help enemy aircraft to locate the royal estate. Over the course of several days the Grand Canal was drained and various other fountains were emptied. Only the Lake of the Swiss Guard was left untouched.

“At present we are travelling through a tunnel; we do not know how long it is, or what the landscape will look like on the other side. That God only knows. We must remain patient and trust that better days shall come, eventually…”

Pierre Ladoué, head curator of the Palace of Versailles to Gaston Brière, his predecessor and supervisor of the Brissac depot, Versailles, 5 October 1939

For several months the palace lived shut off from the world, stripped of a large part of its collections and décors. Works not suitable for transportation, such as the ceiling paintings, were left in situ. But as the “phoney war” dragged on, some people began to question the wisdom of keeping the palace closed, and called for it to be reopened. Behind the scenes, the tension between the head curator and the architect in chief was becoming increasingly acute.

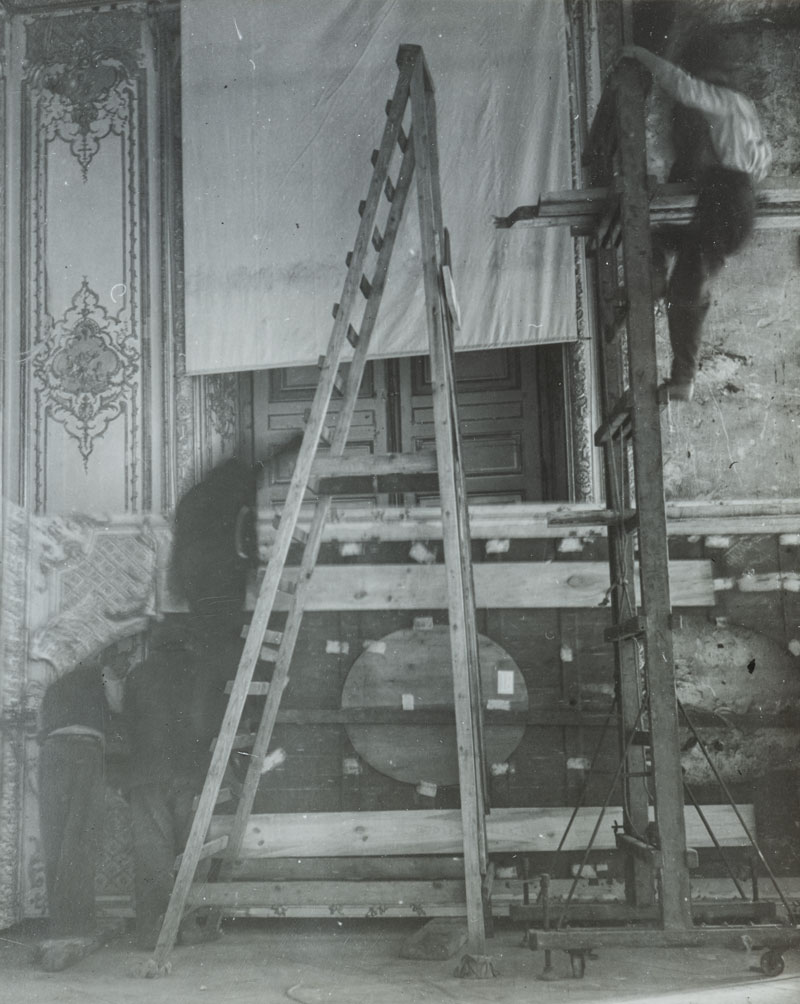

Dismantling the wood panelling in the Queen’s Chambers, Autumn 1939 © Archives of the Palace of Versailles

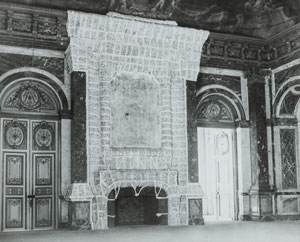

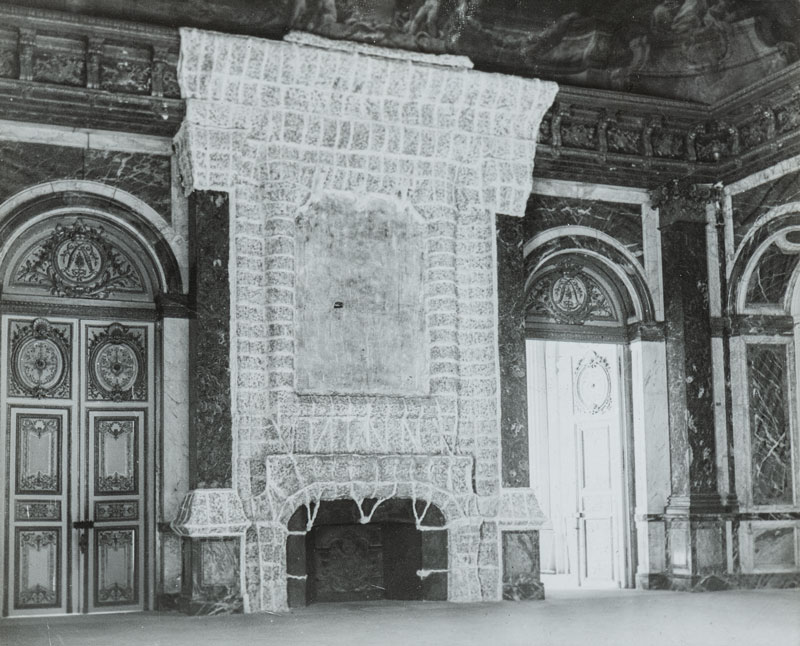

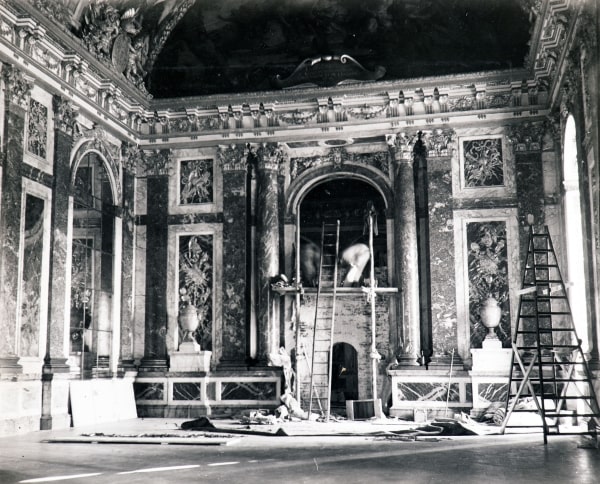

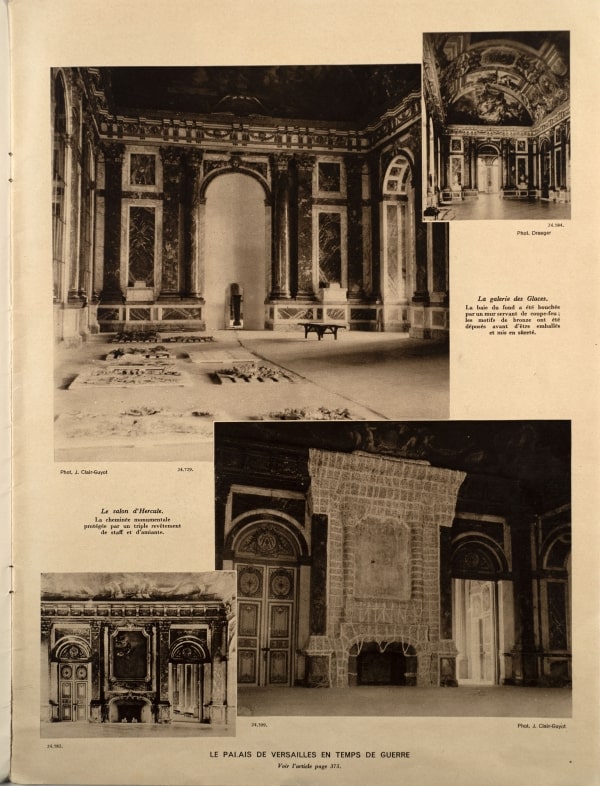

Since it could not be removed, the fireplace in the Hercules Room was fireproofed with a triple-layered coat of staff and asbestos © Archives of the Palace of Versailles

7 October 1939

By early October, hundreds of works from the museum’s collections had already left the estate: 494 paintings, 32 tapestries and carpets, 85 smaller artworks, 52 curtain wall hangings and 32 pieces of furniture (a total of 695 items).

Autumn 1939: blacking out the windows of the palace

Inside the palace, the broad window bays of the Hall of Mirrors were closed off with thick brick walls. The sculpted décors were dismantled, numbered and packed up; the fireplaces – which could not be transported – were fireproofed. In order to protect against potential bomb damage, windows looking out onto the town and the gardens were boarded up with thick wooden panels with fire resistant coatings, reinforced with sandbags. In the Autumn of 1939, the Palace of Versailles was plunged into darkness.

Boarding up the windows on the courtyard side © Archives of the Palace of Versailles

Boarding up the windows on the garden side © Archives of the Palace of Versailles

“ The palace is putting the finishing touches to its wartime attire. It is dreadful. The leaves are falling in the gardens, gathering on the naked plinths. The wood panels are gradually being stripped off the walls. We are roaming about the place with lanterns, since all of the windows have been blacked out, wandering through rooms with pitiful bare walls, yet still capped off with golden ceilings… We wish you both strength and fortitude in these dark times. Better days will come, of that we can be sure. ”

Pierre Ladoué, head curator of the Palace of Versailles, to Gaston Brière, Versailles, 5 October 1939

November 1939: the first cases of wood panels left the palace aboard a fleet of trucks

Patrice Bonnet requested additional funds from the Directorate General for Fine Arts. This request was turned down, and the architect was instructed to adapt his plans and halt the dismantling of the palace’s wood panelling. Bonnet had to admit that the first round of removals had been hastily conducted, due to the lack of a detailed plan, but reiterated the seriousness of the situation.

“ An error of judgement may be excused if no bombs damage or destroy Versailles, but any lack of initiative will be unforgivable if the worst should come to pass. ”

Patrice Bonnet to the Director General for Fine Arts, February 1940

24 November 1939: Le Figaro, ‘Versailles Wiped off the Map’ » The French press was becoming increasingly critical of the passive defence measures put in place at Versailles. Many commentators criticised the decision to close the palace and the estate, and bemoaned the damage done. This grumbling culminated in an editorial published in Le Figaro on 24 November, challenging the justification for these protective measures.

Versailles, gardens of Paris ; Versailles, regular place of promenade for the people of Paris. They used to come here, even in winter, every Saturday afternoon and Sunday to visit the Palace, and above all to walk across the gardens.

The Palace and the gardens are now closed, since the war, and the people of Versailles are lamenting, especially the merchants, who mainly live thanks to this Sunday invasion… « We are no longer visited by people, and our french or foreign hosts are leaving us, one by one, they said. The Chamber of Commerce and the municipality objected, unsucessfully… Why? »

Indeed, we do not understand the closing of the Palace of Versailles, which is, for sure, a huge disaster for the city.

Let’s keep closed the rooms in which we cannot see paintings already evacuated… But why must we keep closed the Hall of Mirrors, Hercules Room, the King’s and Queen’s State apartments? Above all, why must we keep the park closed? The guardians are all retired or disabled from the last war, they are no longer susceptible to be send to the front… So? Do we keep closed the public gardens in Paris?

Would Hitler have also wiped the Palace of Versailles off the map?

Le Figaro, 24 November 1939 © BnF-Gallica / © Bibliothèque Nationale de France

9 December 1939Facing down these increasingly virulent attacks, Patrice Bonnet decided to respond in print. He published an article in L’Illustration insisting upon the irreparable losses that would be sustained were any of Versailles’ art collections to be destroyed. The nature of these priceless artefacts, he argued, was such that « today’s craftsmanship, no matter how skilled, would be incapable of reproducing them ».

Winter 1939/1940Throughout the Winter of 1939-1940, the palace was left unheated. Window panes had been removed to make way for sandbags, allowing the cold air to invade the interiors. Frost soon formed in several of the rooms. In early 1940, this frost thawed and caused some severe damage: ceilings gave way, with water running down the walls and damaging a number of paintings, particularly in the Gallery of Great Battles.

27 March 1940: the wood panelling is stripped from the Queen’s Bedchamber, the Clock Room and the Council Chamber.

10 May 1940: the ‘phoney war’ is over

In May 1940, with German forces making rapid advances, the people of France began fleeing south. In Versailles, a dozen of the remaining museum attendants left the palace and headed to Brissac with their families. The staff remaining on site was spread across the estate: Ladoué and Bonnet in the palace, with Mauricheau-Beaupré overseeing affairs at the Grand and Petit Trianon palaces; around twenty attendants and groundskeepers remained on site. But a sense of panic was beginning to grip Versailles…

Château de Brissac © private collection (© EPV/Didier Saulnier)

Château de Sourches © Archives nationales (20144792/253)

3 June 1940: the Luftwaffe bomb Versailles. Three shells land close to the Royal Opera House, on Avenue de Paris and Rue des Réservoirs

9 June 1940 : the majority of the remaining employees leave Versailles and head south (Chambord, Brissac, Valençay)

13 June 1940 : exodus of the local population fleeing Versailles.

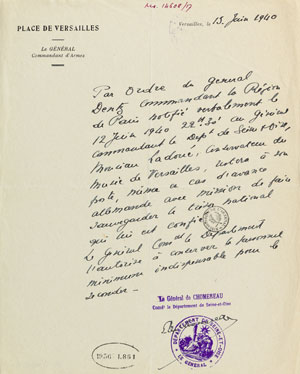

By 13 June, Versailles had become a ghost town. Patrice Bonnet decided to abandon his post; at the palace, following the departure of his deputy Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré, Pierre Ladoué was the sole figure of authority. The vast majority of the estate's employees had by now fled as far from the capital as possible. Only for men stayed behind to defend the vast estate: Pierre Ladoué, Victorien Cessac, Louis Borel and Henri Dudognon.

“ This time, Hitler will not have Wilhelm’s good grace to spare the ‘city of water’… dead water… May the spirit of Louis XIV protect Versailles! ”

Gaston Brière to Pierre Ladoué, Brissac, 5 June 1940.

14 June 1940 (07:00): the gunpowder store at the Satory military camp explodes

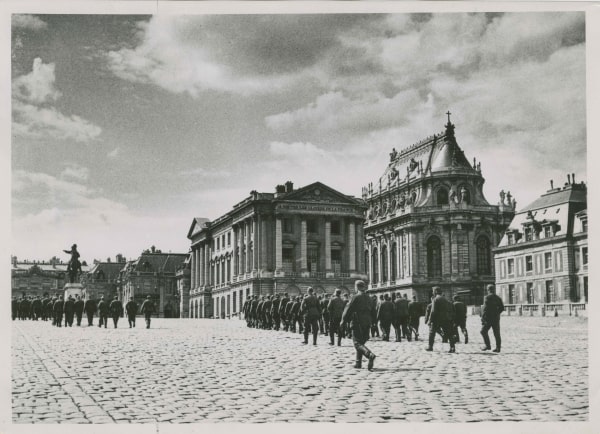

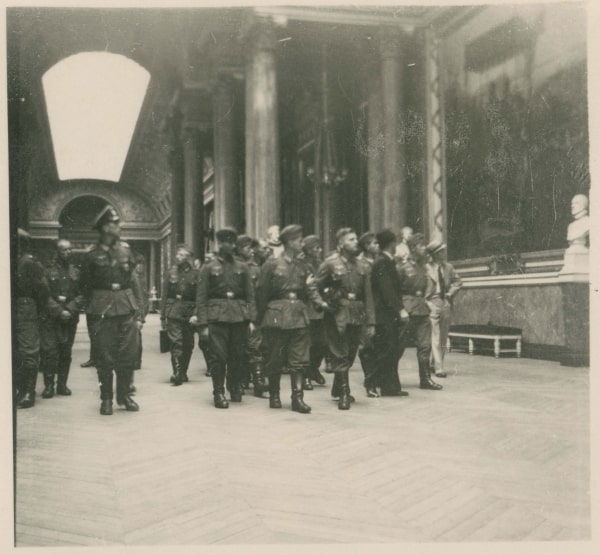

The Wehrmacht enters Versailles

“ At twenty to ten we witnessed the first act of a painful, humiliating occupation which would last for four interminable years. Amid a deafening din of explosions and the crunch of tank tracks, the motorised and armoured columns of the swaggering Wehrmacht descended the two main avenues of Louis XIV’s town. ”

Marcel Petit, L’occupation et la libération de Versailles, Les Editions du Choix français.

15 June 1940: the swastika flag flies over Versailles.Victorien Cessac, one of the few remaining attendants, is ordered by German soldiers to take them to the highest rooftop of the palace, where they raise the Nazi flag.

“ The Place d’Armes was swarming with soldiers in green uniforms, the crowd growing bigger by the minute. We estimated there must have been 10,000 men. Like a roiling sea they beat against the gates of the palace’s Honour Courtyard (…) They soon lost their patience with these closed gates, and began shaking them furiously. ”

Marcel Petit, L’Occupation et la Libération de Versailles, Les Editions du Choix français.

16 June 1940: Philippe Pétain becomes Prime Minister

18 June 1940: General de Gaulle issues his famous rallying cry.On the very day that General de Gaulle issued his rallying cry, the Germans were busy installing anti-aircraft guns in the gardens of the palace. Versailles was becoming a militarised zone…

Link to the Collections

22 June 1940: Philippe Pétain signs the armistice agreement with Germany

27 June 1940 : the Kommandantur takes up residence at the Hôtel de Ville in Versailles

1st July 1940: Joseph Goebbels visits the Palace of Versailles and the Grand Trianon.

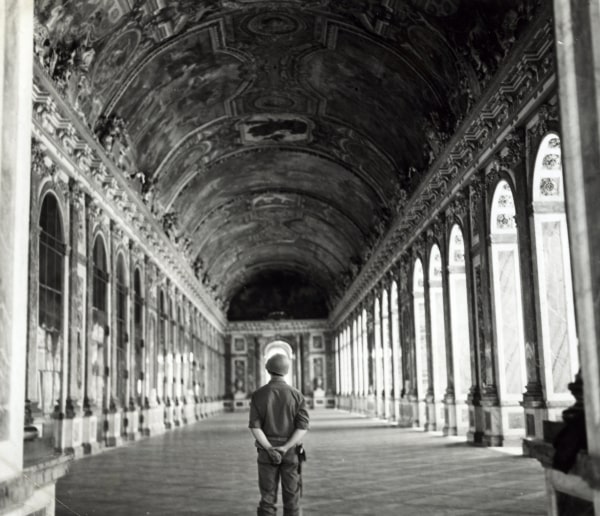

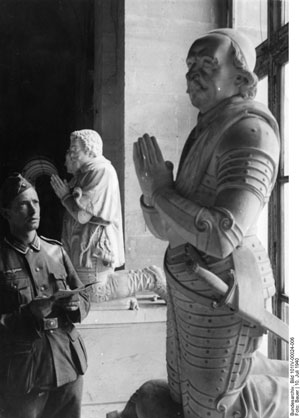

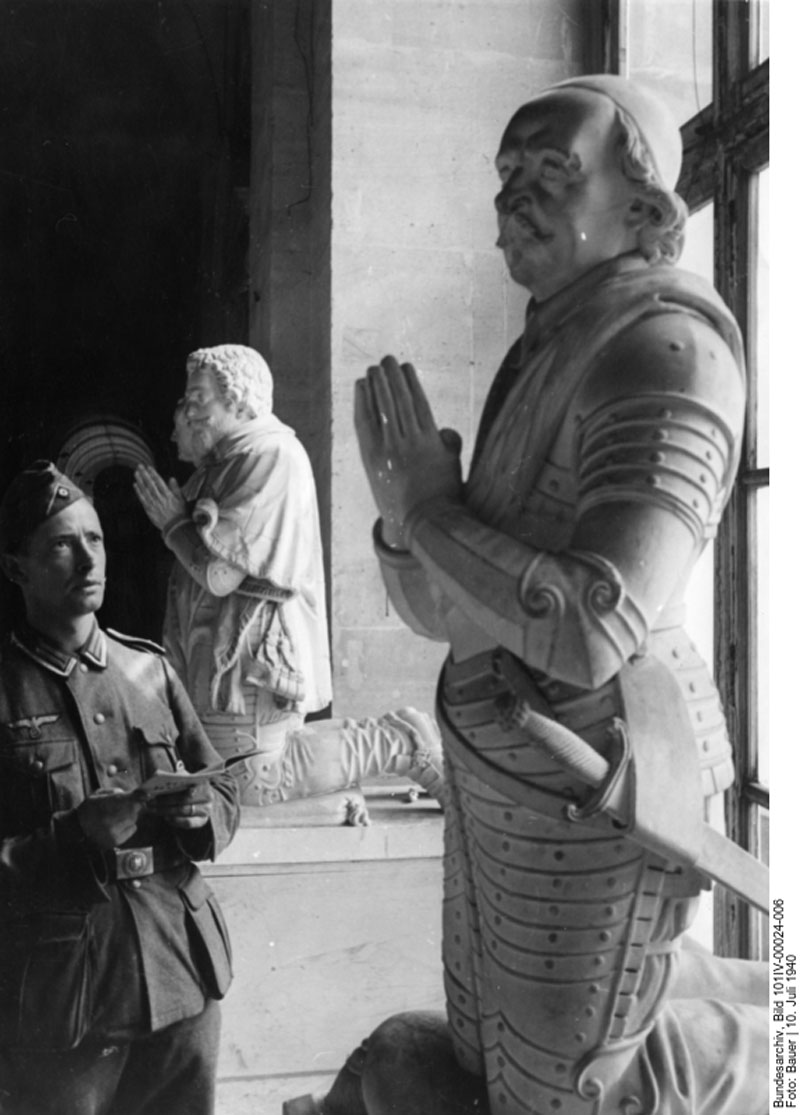

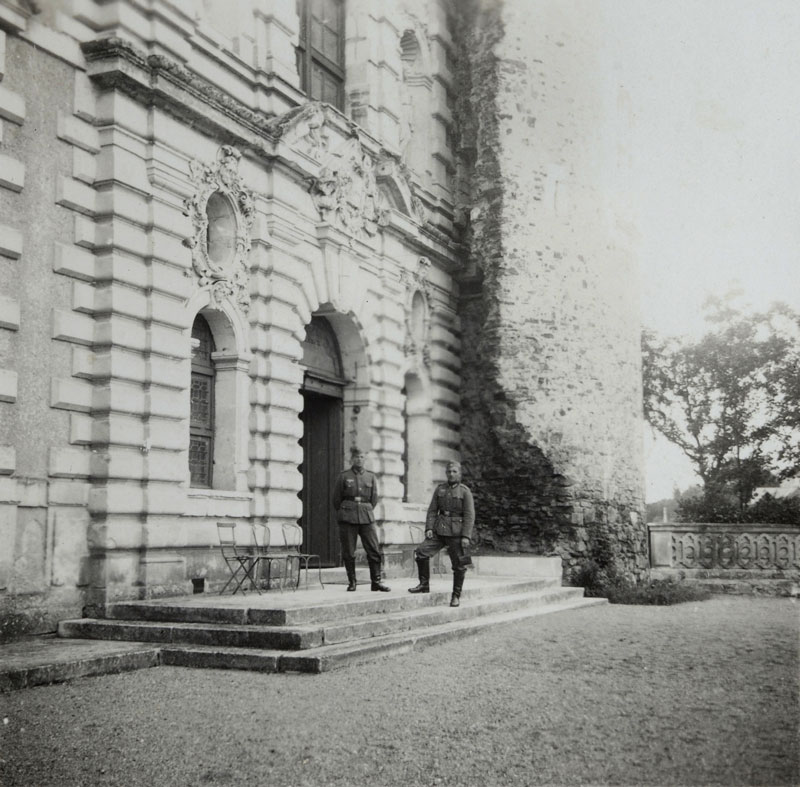

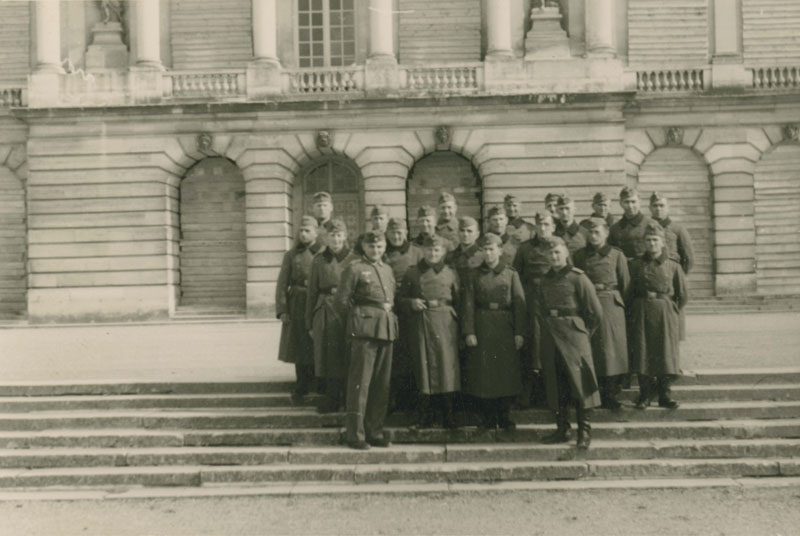

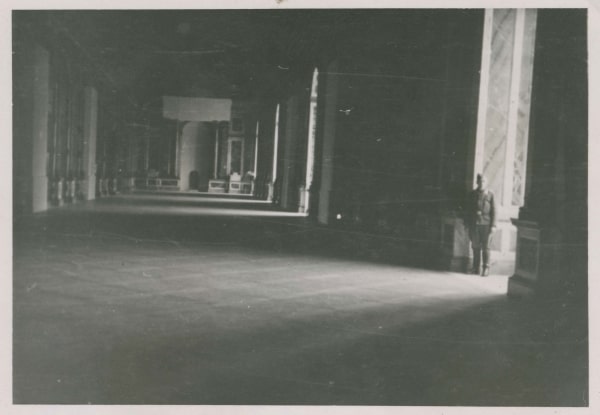

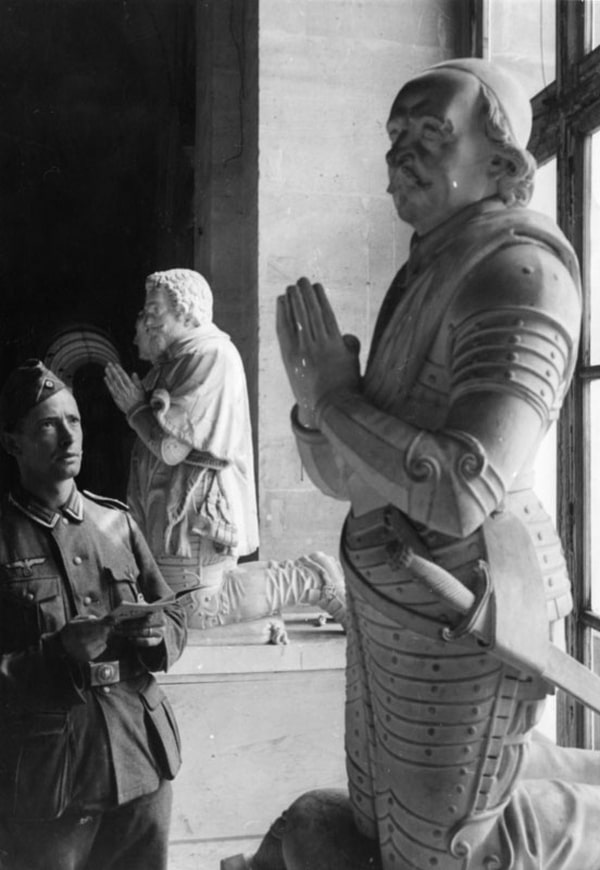

Throughout the summer of 1940, a large number of German troops visited the Palace of Versailles. The soldiers eagerly explored the historic surroundings, particularly the famous Hall of Mirrors. In the Orangery and the gardens, on the terraces and in the State Apartments, the invading troops posed for photographs, individually and in groups.

“ Versailles is no longer ours. ”

Pierre Ladoué to Gaston Brière, Versailles, 21 July 1940.

With Versailles now declared an “open city,” the Wehrmacht began to make itself at home, particularly in the stables. Life went on, but the German domination was clear to see. Even the road signs were now written in French and German.

The Palace of Versailles from the Avenue de Paris, 1940-1942 © Bildarchiv Marburg

The Palace of Versailles from the Avenue de Paris, 1940-1944 © Archives of the Palace of Versailles

Link to the Collections

5 July 1940: a concert and torchlit march were organised in the Honour Courtyard

11 July 1940: in a radio broadcast, Philippe Pétain announced his intention to make Versailles the seat of his government.Initial plans were made to set up the government in the palace itself, or at the Grand Trianon.

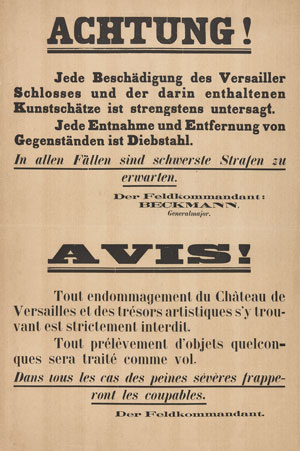

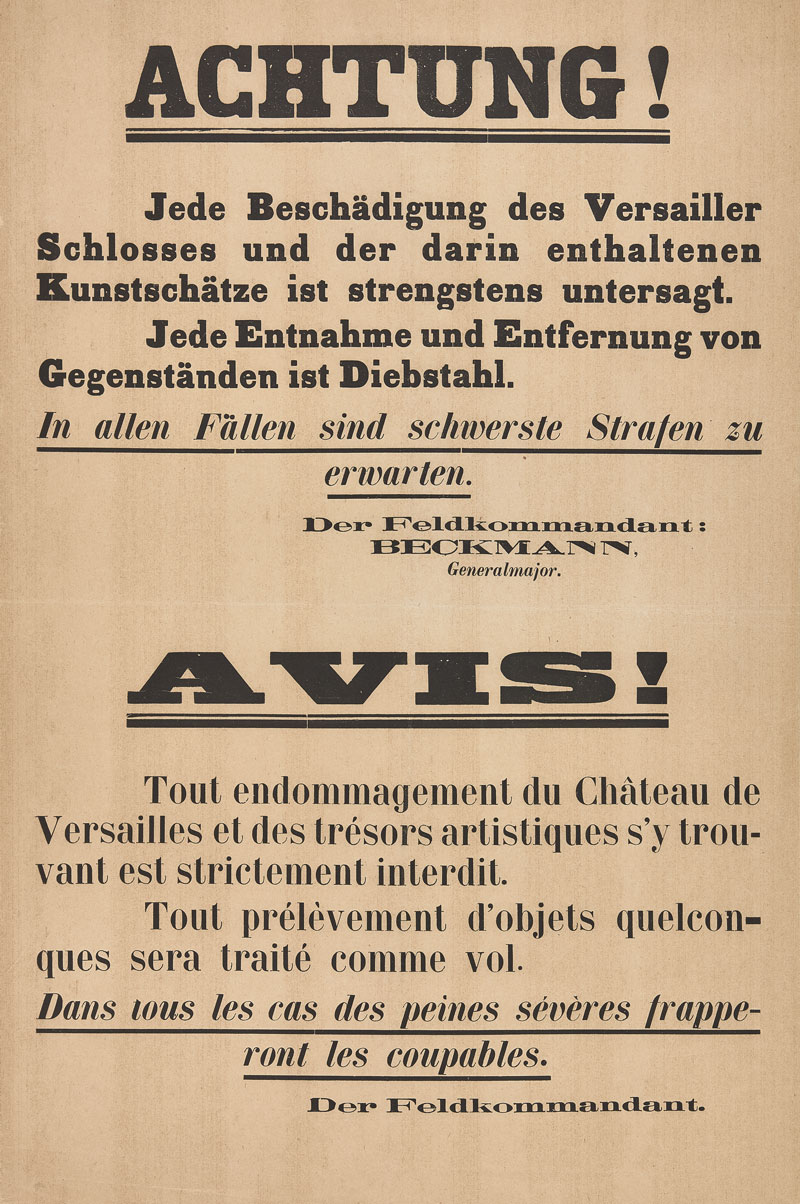

July 1940Within hours of the German occupation beginning, Versailles was counting the cost of the damage inflicted by some of the soldiers. Pierre Ladoué complained bitterly of this damage: lacerated paintings, missing door handles, stolen artefacts etc. In response to the repeated complaints of the head curator, the Kommandantur set up an authorised visitor route with signs in French and German. Fewer incidents of damage were recorded thereafter.Patrice Bonnet and Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré returned to Versailles.

August 1940In August, Franz Graf Wolff Metternich, a Francophile and an experienced curator, was appointed as head of the Kunstschutz, the Commission for the Protection of Artworks in Occupied Territories. As soon as he arrived in Paris he began to work with Jacques Jaujard, who was now Director of the National Museums. They built up a relationship of mutual trust, which contributed to the preservation of the national collections.

29 September 1940: the architect in chief of the Palace of Versailles, Patrice Bonnet, was forced to resign. He was replaced by his colleague André Japy.

7 October 1940: Pierre Ladoué, head curator of the Palace of Versailles, resigned his post. He was replaced by his deputy, Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré.

This shake-up in the palace’s senior management was partly due to pressure from the German authorities. As soon as they arrived the Germans began complaining about the pitiful condition of the palace: the rooms were empty, the works sent into exile, the gardens altered beyond recognition. The occupying authorities began to exert pressure upon Jacques Jaujard, and particularly André Japy and Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré: they wanted to see the palace and gardens restored to their former glory.

October 1940Ultimately, it was in the vicinity of the Trianon Palace hotel that a villa was prepared for Marshal Pétain. The logistical challenges involved were many and various, and criticism of the move further delayed Pétain’s plans to base himself in the former royal city, something of which the German authorities disapproved.

Night of 25-26 October: a German Heinkel 111 crash landed on the Frog Lawn, on the Trianon estate. None of the plane’s occupants survived.

December 1940: having been refused permission by the German authorities, Marshal Pétain abandoned plans to base his government in Versailles. Vichy, in the unoccupied zone, remained the seat of government.

January 1941: André Japy begins reversing passive defence measures in the Hall of Mirrors

As work commenced to restore the palace to its former glory, thawing frost caused serious damage to the upper floors: water seeped in through the roof, trickled down through the ceilings and in some places reached the ground floor. The Gallery of Great Battles, where almost all of the grand paintings had been left in situ, was particularly exposed to the vicissitudes of this harsh winter.

“ I have the honour of informing you that, as a result of the sudden change in temperature arriving after a long period of frost and snowfall, accidents have occurred at several museums, particularly Versailles […] In spite of our repeated efforts, our inability to secure sufficient fuel for the heating of these establishments has necessarily exacerbated the consequences of the weather conditions we have endured in recent weeks. ”

Jacques Jaujard, Director of the Louvre and National Museums, to the Director General for Fine Arts, Paris, 25 January 1941

30 January 1941: Jacques Jaujard asks Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré to draft a plan for “re-establishing the museum at Versailles.”The curator now found himself faced with the immense task of restructuring the museum. As he saw it, the absence of a large proportion of the collections represented an opportunity to entirely rethink the nature of the institution, and give it a new direction.

“ The Museum of Versailles is not just for scholars and experts; above all, it should be a visual illustration of our history for our children and foreign visitors. Only then does the lesson come to life […] This new direction, and the importance the head of state attaches to the teaching of History, have inspired us to give renewed prominence to the grand historical compositions of the Romantic painters. Although their veracity as historical sources may sometimes be doubtful, their educational value remains certain. ”

Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré, report on the restructuring of the museum at Versailles and the presentation of the rooms of the Palace of Versailles and the Trianon Palaces, Versailles, 24 March 1941

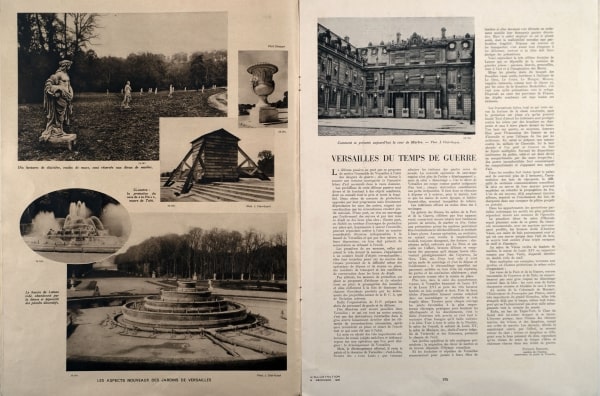

Spring 1941: work to restore the gardensAndré Japy oversaw the return of the statuary, which had been shipped off in Autumn 1939 to the Abbaye des Vaux-de-Cernay. The statues were gradually restored to their original positions. In the gardens, work was needed to clean up the alleys and remove the long grass and piles of dead leaves.

Due to a lack of upkeep, the gardens of Versailles were covered in dead leaves, 1941-1943 © Emmanuel-Louis Mas (1891-1979) © Ministry of Culture (France), Médiathèque de l'architecture et du patrimoine, RMN-GP

Allée des Marmousets, 1941-1943 © Emmanuel-Louis Mas (1891-1979) © Ministry of Culture (France), Médiathèque de l'architecture et du patrimoine, RMN-GP

“ Mr. Bonnet’s successor is already working on recovering the various artworks and putting them back in place. This work will be made easier by the orderly, methodical manner in which the preceding operations were conducted. We will soon be reacquainted with those cherished statues of marble, bronze and lead which have long adorned the lawns, groves and fountains; in the hallowed halls of the palace, the mirrors, marbles and bronze will soon sparkle once again. Versailles, beloved of artists and poets, will be returned to us so that we might love and admire her more than ever before, if that were possible. ”

Henri Puvis de Chavanne, ‘Versailles and the war’, Beaux-Arts, Le Journal Des Arts, 10 January 1941

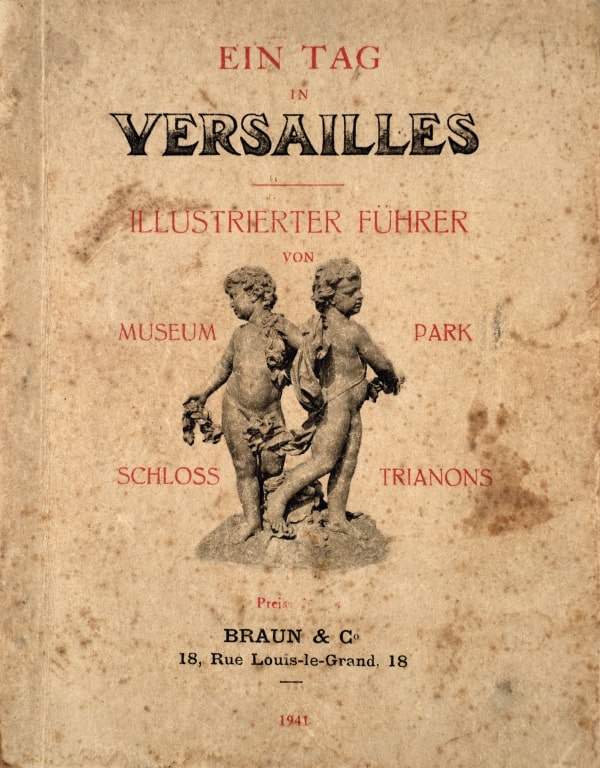

1st June 1941: part of the palace reopens to the public, specifically the north wingCharles Mauricheau-Beaupré oversaw the reopening of the museum to the French public, including the 17th-century rooms, ten new rooms dedicated to the 19th century and a small room devoted to the last war. The State Apartments, however, were only open to German soldiers. Visitor guides in German rapidly sold out, and had to be reprinted.

Visitor guides to the Palace of Versailles, Braun 1941 edition © private collection

German soldier visiting the lower gallery, guide book in hand © Bildarchiv

German soldiers guarding the entrance to the Palace of Versailles, 1941-1943 © Bildarchiv Marburg

10 August 1941: the garden groves reopen to the publicAlthough the “petit parc” reopened to the public, the Grand Park had been damaged by local people chopping down trees for fuel. The Grand Canal, drained in the Autumn of 1939, was filled with long grass. Its banks were also crumbling due to a lack of upkeep.

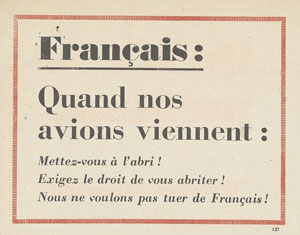

27 August 1941: resistance fighter Paul Colette shoots Pierre LavalDuring a visit to the military barracks at Borgnis-Desbordes in Versailles, Paul Collette attempted to assassinate Pierre Laval, former deputy prime minister of the Vichy government. Laval was injured in the attack. The atmosphere was by now more tense in Versailles, as it was all over Europe: the Luftwaffe was an increasingly ominous presence in the skies. At the palace, the fear of bombing was still very real.

Autumn 1941: due to a lack of staff, the Petit Trianon is closed to the publicThe condition of the Petit Trianon was deteriorating, and the remaining staff found themselves in a difficult position. With Winter approaching, there were no plans to supply the palace with coal. With no fuel, the night-time patrols were often conducted in total darkness.

January 1942: thawing frosts caused yet more damage in the North Attic. Paintings were taken down and the attic was closed.Some paintings were damaged by the cold, while others suffered as a result of the damp conditions and the lack of light from the boarded-up windows. Water trickled in; the gutters clogged up; the ceiling of Madame de Pompadour’s bedroom threatened to cave in… In the Spring of 1942, Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré authored an alarming report on the current state of the collections, while continuing his attempts to restore the palace to its former condition.

“ It is fair to say that water is coming in all over the palace, through the ceilings and glass ceilings, causing damage to the collections on a scale which cannot yet be assessed. ”

Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré to Jacques Jaujard, 31 January 1942

2-3 March 1942: collapse of the glass ceilings in the Chimay Attic, the South Attic and the Royal Tennis Court

3 March 1942: Portrait of Marshal Pétain brought back to the palace from the Sourches depot by André Devambez.Listed in the collections of the palace since 1931, the Portrait of Marshal Pétain, subsequently transferred to the Château de Sourches for safekeeping, was returned to the Palace of Versailles at the request of Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré. The curator had it reframed in a large gilt creation bearing the francisque symbol and the marshal’s coat of arms. In June, this portrait was hung in the corridor of the gallery in the North Wing.

Night of 5-6 March 1942: collapse of the central medallion from the ceiling of the Queen’s Guard Room.For months, Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré had been warning the National Museums Directorate of the risks induced by the regular machine gun fire emanating from German anti-aircraft positions on the terraces of the palace gardens. In the night of 2-3 March 1942, the glass roof panels of the Chimay Attic and the Midi Attic collapsed. Two days later, part of the painted ceiling of the Queen’s Guard Room gave way. In May 1942, closer inspection of the ceilings in the State Apartments showed them to be in imminent danger of collapsing.

Summer 1942The curator continued with his efforts to restructure Versailles and expand the museum’s collections, by means of acquisitions and donations. He was also planning a new exhibition focusing on Napoleon.

“ We need to take advantage of this enforced period of closure to conduct this sort of restoration work, which will be very difficult on all fronts – not least the impact on public opinion – when we are obliged to reopen the State Apartments and let people visit the palace. ”

Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré to Jacques Jaujard, Versailles, 26 September 1942

With manpower hard to come by, the task of clearing excess vegetation on the edges of the gardens was entrusted to a flock of sheep. They were also allowed to graze along the banks of the Grand Canal.

11 November 1942: German troops invade the unoccupied zone; Hitler officially approves Marshal Pétain’s request to relocate to Versailles, although the latter declines to act upon this invitation.

January 1943The palace faces a third successive winter without heating. Inside, the ceilings are still threatening to cave in. During the winter months, deteriorating conditions in the Trianon Palace lead to the return of some forty paintings to the main palace.

13 January 1943: Hitler announces that Germany is now engaged in a “total war”In France, the conditions of the Occupation were becoming harder to bear. At Versailles, the militarisation of the estate continued despite the fact that the gardens were open to the public. The occupying authorities made plans to install launching platforms on the Trianon estate; the gardens were repeatedly disfigured by military vehicles, which caused considerable damage to the alleys. With the risk of bombing still a real concern, the prefect advised Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré to cap visitor numbers with reference to the capacity of the air raid shelters.

“ We are aghast, and my natural pessimism has been outstripped by actual events. Never would I have believed that we could stoop lower than the shame of June 1940. For now we must hold our tongues, clench our fists and wait. The day will soon come when our country shall renew with its history and forge a new destiny worthy of its past. I console myself with this hope, and devote my thoughts, like Candide, to tending our beautiful garden here in Versailles. ”

Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré to Gaston Brière, Versailles, 20 January 1943

The threat from the skies was not the only danger faced by the palace. In particular, the risk of famine was a very real problem for the staff working at Versailles. Malnutrition and troubles with food supplies made it necessary to use every last plot of available land on the grounds.

“ Here, the only thing keeping us from dying of hunger is the gardens. There is next to nothing to be had at the markets… ”

Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré to Gaston Brière, Versailles, 28 January 1943

“ My doctor is urging me to ‘drop everything and focus on getting in supplies’, which is dreadful. If you know of anyone in your region willing to send packages, I will pay for butter or meat or anything, any sort of fat: we are worn down to the bone. ”

Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré to Gaston Brière, Versailles, 26 March 1943

15 March 1943: Hermann Goering visits the palace. This was one of several visits made by Goering during the Occupation, always travelling incognito

3 June 1943: the Orangery hosts a celebration for Mothers’ Day, a theme promoted by the Vichy regime

19 juin 1943: the Luftwaffe install an anti-aircraft gun on the roof of the Great Stable

22 June 1943: a broken pipe causes a serious leak above the Coronation Chamber

Versailles was becoming increasingly militarised, while the palace itself continued to suffer as a result of the harsh conditions of recent winters and the large numbers of the occupying forces. Concerned by the damage, some of France’s most senior political figures appealed to the conscience of the German authorities.

“ In light of the place which the Palace of Versailles occupies within France’s artistic heritage, it is my duty to draw your attention to the importance of ensuring that the national estate is safeguarded and exempted from any form of requisition. ”

Louis Hautecoeur to the president of the German Commission, 24 June 1943

23 February 1944: the Gestapo raid the Trianon

The German military police spent almost two hours searching the home of the head curator, on the Grand Trianon estate, suspecting Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré's son Jean of ties to the Resistance. Jean Mauricheau-Beaupré was indeed a member of the Resistance, but fortunately he was able to flee before the Germans arrived.

Night of 26-27 April 1944: a flaming projectile lands in the courtyard of the palace, just in front of the pavilion on the south side of the Ministers’ Wing.

Bombs over Versailles

In the town, the air raid sirens sounded almost every day. Bombing became a very real threat, and the presence of German anti-aircraft guns on the royal estate only accentuated the risk. On the evening of 4 June 1944, around 8:15pm, Allied bombers unloaded on Versailles. The Allied bombs were directed at infrastructure targets – particularly train stations – but many shells fell close to the palace: in the Saint-Louis district, around the Matelots train station and on the Route de St-Cyr. Almost 50 bombs fell in the gardens, further damaging the banks of the Grand Canal.

D-Day landings in Normandy

Night of 7-8 June 1944: more bombs fall on Versailles. The neighbouring town of Saint-Cyr suffers substantial damage.

Faced with this new danger, Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré adopted new measures to protect the palace and its collections. The fountains closest to the main palace and the Trianon palaces were refilled with water, for use in the event of a fire.The Wehrmacht, meanwhile, continued their intrusions into the gardens of Versailles.

“ It is an absolute disaster. Tanks and armoured cars have forced their way into the forest, breaking everything in their path and destroying the alleys. The Occupying forces have hacked down whole rows of trees, leaving stumps a metre high. ”

Report of Adjutant Pierre Lasal to André Japy, Versailles, 20 June 1944

15 June 1944: museum attendant Yves le Foll killed during Allied bombing of Saint-Cyr

22 June 1944: Saint-Cyr bombed again

On 23 June, Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré organised a mass in memory of Yves Le Foll at the Saint-Louis Cathedral in Versailles. The chapel of the military school at Saint-Cyr had been completely destroyed, but an urn containing the remains of Madame de Maintenon somehow emerged intact from the ruins.

“ I immediately had it transferred to the chapel, where I arranged a temporary sarcophagus in the St-Louis chapel. What a remarkable destiny this woman has known. Even after death, to withstand the bombs and return serenely to the palace, where bodies were never left to dwell! She truly is a woman for exceptional times. ”

Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré to Gaston Brière, Versailles, 12 July 1944

British bombs rain down on Versailles

The RAF bombing raids primarily focused on infrastructure targets. In Versailles, the Chantiers station was hit on several occasions in June 1944: more than 220 victims died there on 24 June, and 250 more on 29 June.

July 1944: an air raid shelter-trench was dug in the Trianon gardens, to protect the local population from bombing.

Allied bombing raids became increasingly frequent in August, and the German army began to park their vehicles in the gardens of the palace, ignoring the protestations of Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré and André Japy. The Germans cut down branches from the trees to camouflage their vehicles; local people made the most of this unauthorised logging, stealing the unused wood. The failing supply of basic materials remained a vital problem for the local population in Versailles.

11 August 1944: Jean-Baptiste Faucher, one of the museum attendants from Versailles seconded to the depot at the Château de Brissac, is executed by the Germans

12 August 1944: the train line to Paris is blocked

17 August 1944: the mayor and bishop of Versailles publish a joint appeal to the German troops

“ As the front line moves closer to Versailles, the civil and religious leaders of this historic town which witnessed the apogee of the monarchy (…) address a solemn appeal to the belligerent parties. They enjoin them to regard Versailles as an open city, to respect the peerless artistic treasures found in its palaces and gardens. In its history, its soul, Versailles embodies our past. An entire civilisation is represented here. The histories of our peoples are intertwined here. The destruction of such treasures, such elegance, would be an irreparable loss to humanity. Surely neither the German army, who well remember that the unity of the German Empire was proclaimed in Versailles, nor the American army, who have not forgotten that the independence of the USA was consecrated at Versailles, would wish to stand before the judgement of History and bear the crushing responsibility for such a crime. ”

Mgr Roland-Gosselin, Pierre Revilliod, Gaston Henri-Haye and François Fourcault de Pavant, Appeal to the Belligerents, 17 August 1944

Late August 1944: the last German convoys leave Versailles

24 August 1944: overnight, museum attendant Charles Troussard helps Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré to hide French officers inside the palace

25 August 1944: departing German soldiers unload a volley of machine gun fire on the south-east façade of the palace

The bullets broke a few windows, and some remained lodged in the stone walls. Somehow, the palace escaped serious damage. The tanks led by General Leclerc soon rolled in: Versailles was free, after 1,500 days of German occupation.As the Allied troops poured in, museum attendant Victorien Cessac, the very same man who had been ordered to escort the Germans to the rooftop where they raised the swastika in June 1940, flew the French flag from the roof of the palace.

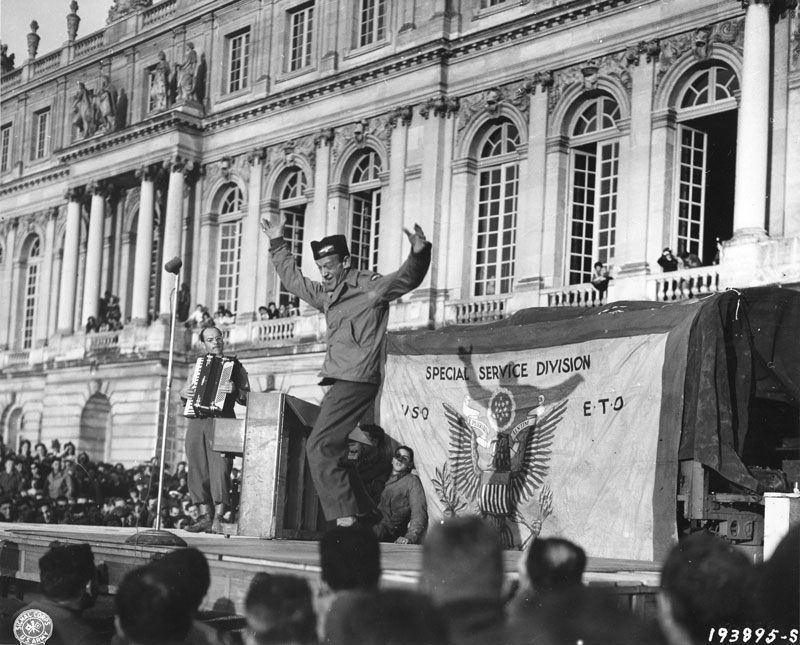

After the departure of the Germans the palace was visited by crowds of British and American soldiers, who now took their turn to stroll through the empty rooms.

A new age was dawning for the royal estate of Versailles, which was soon swarming with American troops. Commander in Chief of the American forces, Dwight Eisenhower set up his HQ in the town. Shortly afterwards the Allied experts in protecting cultural property and historical treasures, the famous Monuments Men, made an appearance.

10 September 1944: Mgr Spellman, archbishop of New York, celebrates mass in the Royal Chapel.

10 September 1944: Fred Astaire and Dinah Shore give a concert in the gardens of the Palace of Versailles

31 January 1945: Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré issues an urgent warning regarding the alarming deterioration of the palace and its collections, badly damaged by the weather conditions and the lack of heating.

“ On 31 January 1945, water seeped in from leaks in the roof. It trickled down the walls of the Gallery of Great Battles, and froze on three of the great paintings: Marignan, Calais and Dunkirk. ”

Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré to Georges Salles, Versailles, 9 February 1945

Germany surrenders

May 1945: the first load of works from the Château de Brissac depot arrives back at Versailles

The gardens are still bustling with visitors, including soldiers who appear to be making themselves at home, causing occasional concern to the French authorities…

“ Mr. Mauricheau-Beaupré has brought to my attention […] a number of regrettable incidents which can be attributed to the rowdiness of the American troops, and which have taken place in the gardens of the palace in recent weeks […] On 20 July, several soldiers climbed up onto one of the large decorative vases on the Midi lawn, masterpieces sculpted by Bertin. The marble vase crumbled under their weight […] ”

Director of France’s national museums to the Prefect of Seine-et-Oise, 7 August 1945

15 June 1945: inauguration of the first exhibition to be held at the palace since 1939, Swedish Artists in France in the 18th century, attracting thousands of visitors.

After the Liberation, certain sections of the museum remained open to the public. Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré began preparations to reopen the State Apartments as soon as possible. He set about restoring the palace to its former glory, continuing efforts to repatriate its furnishings and return the collections to their rightful place. However, a lack of manpower meant that some of the works recovered from the depots were left in their cases.

Summer 1945: the New York Times organises a photo shoot focusing on the work being done to restore the palace’s artworks.

2 December 1945: a section of the ceiling collapses in the Hall of Mirrors

18 December 1945: French newspaper Le Monde publishes a short article on the state of the palace’s ceilings

The final cases of works still held in the wartime depots were returned to the Palace of Versailles in March 1946. Nevertheless, the palace and grounds were still in a sorry state: the building had suffered through a succession of cold winters, and there was much work left to be done.

“ Already the cries of foreboding are ringing out (I’ve often heard them before): Versailles is falling to pieces! … Yes, Versailles has always been fragile. It is a fairy tale palace, a dream, a theatre of illusions. It requires a concerted effort of vigilance and attentive care to keep it alive. Interrupting its upkeep kills the palace (1789-1810…) – 1914-20 – 1940-4 ? – Moreover, we must admit that restoring the masterpiece requires an enlightened imagination; so many alterations have tarnished its beauties. ”

Gaston Brière to Marguerite Jallut, 14 January 1946

Spring 1946: the palace gradually reopens to the public, following extensive repairs and restoration work. The water features are filled again, and the Fountain Shows return.

1st April 1946: 40,000 visitors rediscover the palace over the Easter weekend

1st June 1946 : Charles Mauricheau-Beaupré gives an interview to Le Monde discussing the restructuring of the museum and its reopening to the public

“ Last year we found ourselves looking at the bare walls, with thousands of cases to unpack, and the opportunity to finally commence the comprehensive reconfiguration which we had so much time to mull over during the museum’s period of enforced penitence. ”

July 1946: 60 newly-reorganised rooms are officially presented to the press

10 September 1946: gala reception at the Palace of Versailles during the Paris Peace Conference. On this grand occasion, the Hall of Mirrors rediscovered its pre-war sparkle and fairy tale charm.