Although it was built on marshland, the estate of Versailles paradoxically suffered from a lack of water. Yet throughout his long reign, Louis XIV continued to commission the creation of fountains with increasingly numerous and complex effects. The quest for water thus became something of a long-running saga.

Water at Versailles

At Versailles, where everything was still to be created and the obstacles were seemingly insurmountable, André Le Nôtre, First Gardener to the Sun King, achieved the monumental feat of “taming nature”. The marshy fields and forestland were transformed into gardens described as “the most beautiful in Europe”, further enhanced by fountains boasting the most sophisticated water effects.

The magic of water

Perfected by the Francine family, the famous fountain-makers to Louis XIV, the sheer range of water effects at Versailles was unparalleled: hoses, jets, whirlpools, waterfalls, pools, chasms, and more. The choice of shapes, heights and number of water jets tells the tale of each fountain. And the multiple sounds produced by them – sometimes complemented by decorative items – convey the intense emotions specific to each theme. For example, at the Enceladus Fountain, power and strength are conveyed by large sprays gushing out, evoking the roar of the eponymous giant. The genius of the Francines lay in their ability to combine all these effects yet at the same time separate them, so that the spectator could distinguish between them despite the profusion of water. With its 101 water jets, the Neptune Fountain is the most remarkable example.

By the end of Louis XIV’s reign, the gardens of Versailles counted 1,600 water jets – four times more than now – consuming 6,300 m3 of water per hour. To satisfy this need for water on a site that had none, scientists and academics were mobilised, resulting in the most significant progress in hydraulic techniques since Roman times.

The challenge of water

In the 17th century, knowledge of hydraulics had barely progressed since the Roman Empire, so bringing water to Versailles was a veritable challenge for the engineers of the time. Variations in altitude were only very slight and technical means were rudimentary. Pipes were made of hollowed-out tree trunks, copper and earthenware, and could not withstand high pressure levels. Those made of lead contained too many impurities and would crack regularly. Louis XIV’s ambitions thus led to the development of hydraulic science.

Under his reign, a whole host of pumps, aqueducts, reservoirs and artificial lakes were created. The use of cast iron to make pipes became generalised, and water mills were perfected.

The quest for water required engineers to search so far away that new vision scopes were developed to achieve a new level of precision in tracing and measuring the height of the surrounding land. The aim was to install a hydraulic network based entirely on a gravity collection system, taking water from the higher neighbouring plateaux down to the reservoirs at Versailles.

In 1680, the Sun King called upon the technicians and water engineers of the whole of Europe to find a way to bring the waters of the Seine, 150 metres higher up, down to the gardens of Versailles. It was thus that the Marly Machine was born, five years later. It unfortunately no longer exists.

The Seine to the rescue…

Of all the hydraulic innovations of the time, the Marly Machine was without contest the most spectacular. Outpacing two millennia of water machinery, it was designed by the Liege-based engineer Rennequin Sualem, inspired by the mining pumps of Wallonia. After a successful trial using a smaller model, this gigantic project was launched in 1681. First a dam was built between Bezon and Marly in order to generate a 2-metre high waterfall powerful enough to turn the machine’s 14 paddle wheels. These wheels were 12 metres in diameter and drove pumps positioned on three levels, connected together by a network of chains running 700 metres along the hillsides. Lastly, the Louveciennes aqueduct – 643 metres long – drew water from the Seine and carried it to the Deux Portes reservoir in Versailles. Four years and 1,800 men were required to complete the Marly Machine. The cost was considerable: 3.5 million livres to build it, plus the even higher cost of maintaining it. But the results were ultimately disappointing. After eight new versions, it was definitively scrapped in 1960.

This great adventure, involving research into and the creation of new water networks, came to an end in 1695. The saga had lasted 32 years!

The Fountains Show

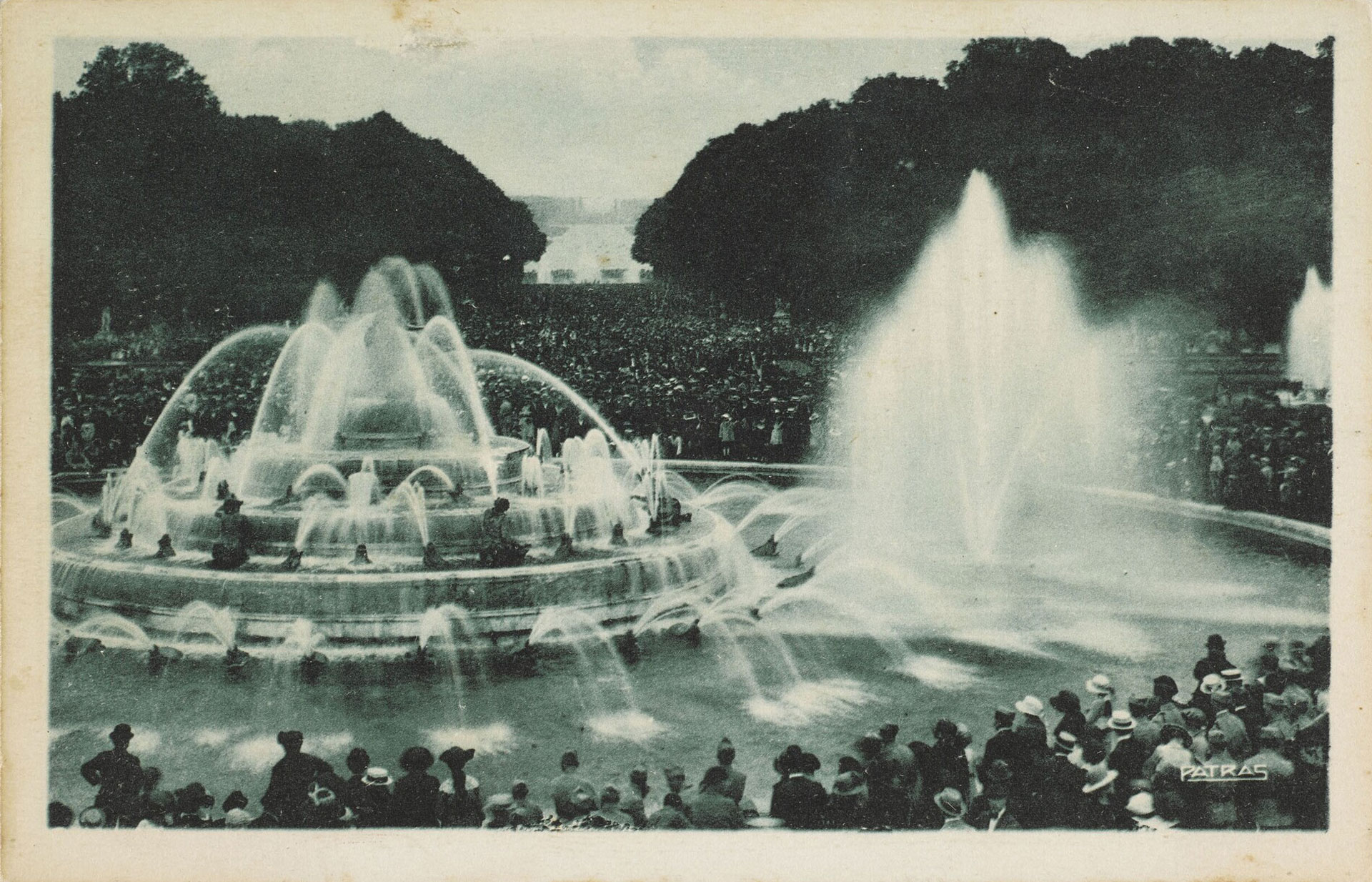

The first Versailles “Fountains Shows” were held on 27 April 1666. The show involved opening all the fountains simultaneously, or at least at the same time that the Sun King passed by them, a moment that was signalled using a whistle.

The fountains created by Louis XIV have been showing off their water effects for more than 350 years now, bringing to life the estate’s gardens peopled with mythological gods. But it was not until the 19th century that the Fountains Shows as we know them today were created. Although the fountains went through a period of disuse after the French Revolution, it only lasted until 1804, coming to an end with the return of festive life introduced by Napoleon Bonaparte.

Festivities around the “water effects” continued to grow in number until 1831. Then, in 1837, the French national railway company was founded, offering quick access from Paris to Versailles. Visitors from Paris and abroad flocked to Versailles, leading to the gradual development of the Fountains Show. By 1855, “Eight or ten times each summer, the announcement of these wonderful shows attracted fifty or sixty thousand sightseers”.

The programme was diversified with the addition of the “Fêtes and illuminations of the gardens of Versailles”, performed by gaslight, along with numerous “Firework displays”. These night-time Fêtes drew huge crowds. Extensive restoration work got underway, to repair both the architecture of the fountains and statues and the hydraulic structures and infrastructure.

The development of technologies and materials allowed the network to be modernised: replacement of the lead conduits by made-to-measure cast iron pipes, and of the ball valves by gate valves.

By 1931 the Fountains Show was held every Sunday, “at the reasonable price of 3,500 francs”. This was despite the lack of water in the reservoirs: operation of the Marly Machine had been suspended following major flooding on the Seine, and the reservoirs were being carefully managed for the needs of the local population. The water used for the Shows came from the artificial lakes created by Louis XIV in Versailles, Rambouillet and Palaiseau, and some was also pumped from the wells that had been dug in 1922 on the Plaine de Croissy, 10 kilometres away. The quantity of water needed for each water jet was 8,500 m3. Currently we consume about a third of that figure.

Musical and Night Shows

Today, the Musical Fountains Shows are as spectacular as Louis XIV wanted them to be. Every weekend from April to November, the groves, which are closed the rest of the time, reveal their beauty to visitors. Talkie-walkies have replaced whistles for the synchronised opening of all the fountains. The fountain engineer responsible for the overall flow ensures that the hydraulic network is working properly, and checks the opening of the water jets and their quality. Made of metal or marble, the sculpted gods, human beings and animals appear to be revived, to the accompaniment of the greatest Baroque composers such as Lully, Charpentier and Couperin.

On Saturdays from June to September, there are also the Fountains Night Shows, where the formal gardens are illuminated by a thousand lights, just like in the former night-time Fêtes. Water and light bring the groves and fountains to life to the sound of the Sun King’s music, in a two-and-a-half-hour fairy-tale stroll: from the Grande Perspective where visitors can admire statues, topiaries and pools, which are also lit up, to the Great Lawn shimmering under the light of monumental flames, to the Ballroom Grove surrounded by a thousand and one candles… And finally, the high point of the show at the Neptune Fountain with its magnificent compositions of water jets, Baroque choreographies and cascades of light, where the grand firework display brings the show to a fitting finale.

The artistry of the Versailles fountain engineers

The Versailles fountain engineers are responsible for preserving and restoring the estate’s water resources. It is a profession that requires them to master both 17th-century techniques – such as ladle welding – and modern cutting-edge technologies. It has been officially recognised as a craft since March 2014. Today there are seven of these engineers working on the fountains at Versailles, Trianon, Marly, and Saint-Cloud, restoring the infrastructure and ensuring that it functions properly.

Most of the fountains are still operated manually, via the use of a special wrench to turn the squares above the “Versailles” valves which, unusually, have to be opened clockwise. But some of the fountains are fully automatic thanks to the addition over the decades of latest-generation equipment.

This combination of traditional techniques and contemporary technologies can also be found in the way the water flow is organised. While this is essentially done in the same way as it was in the Louis XIV period, i.e. via gravity, modern closed-circuit pumps have also been installed: they pump water from the Grand Canal to the Montbauron reservoir, from which it then gradually flows to the fountains.

The current underground network contains 35 kilometers of pipes, bringing 9,000 m3 of water to the fountains during the two-and-a-half-hour show.