The French Revolution did not just happen in one day. The whole period, which really began in 1789, was one of profound political, social and economic upheaval in France. The Palace of Versailles found itself right in the middle of all this change and, today, the museum’s collections bear traces of this key episode in France’s history.

Versailles at the heart of the French Revolution 1789

the context

Louis XVI acceded to the French throne on 10 May 1774, upon the death of his grandfather, Louis XV. At this point, towards the end of the 18th century, the French court, with Versailles as its epicentre, was one of the most dazzling in Europe.

But the court system established by Louis XIV and continued by Louis XV and Louis XVI was starting to become expensive, and the public was becoming increasingly agitated over what it saw as waste. The king was aware of this and undertook various reforms, with the help of his comptroller general of finances, Turgot. The kingdom of France’s expenditure was cut right back, as was the lifestyle of the members of the royal family.

The King’s Household was completely overhauled. Turgot, remaining true to his liberal principles, removed trade barriers and price-fixing on grain. But bad harvests and price increases led to riots and revolt in the provinces and the Paris region. Forced to resign, Turgot handed over to Jacques Necker in 1776. The new financial comptroller decided to adopt a more rigorous economic policy.

The many attempts at reform, however necessary, were seen as heavy-handed and so they failed. Public opinion associated this economic crisis with the monarchy itself. As a result of Louis XVI’s indecision and the general contempt for Marie-Antoinette, the blame for the crisis ended up being laid at the young couple’s door.

The meeting of the estates general

The prevailing instability and growing political dissent forced Louis XVI to summon the Estates General which opened on 5 May 1789 at the Menus-Plaisirs building in Versailles.

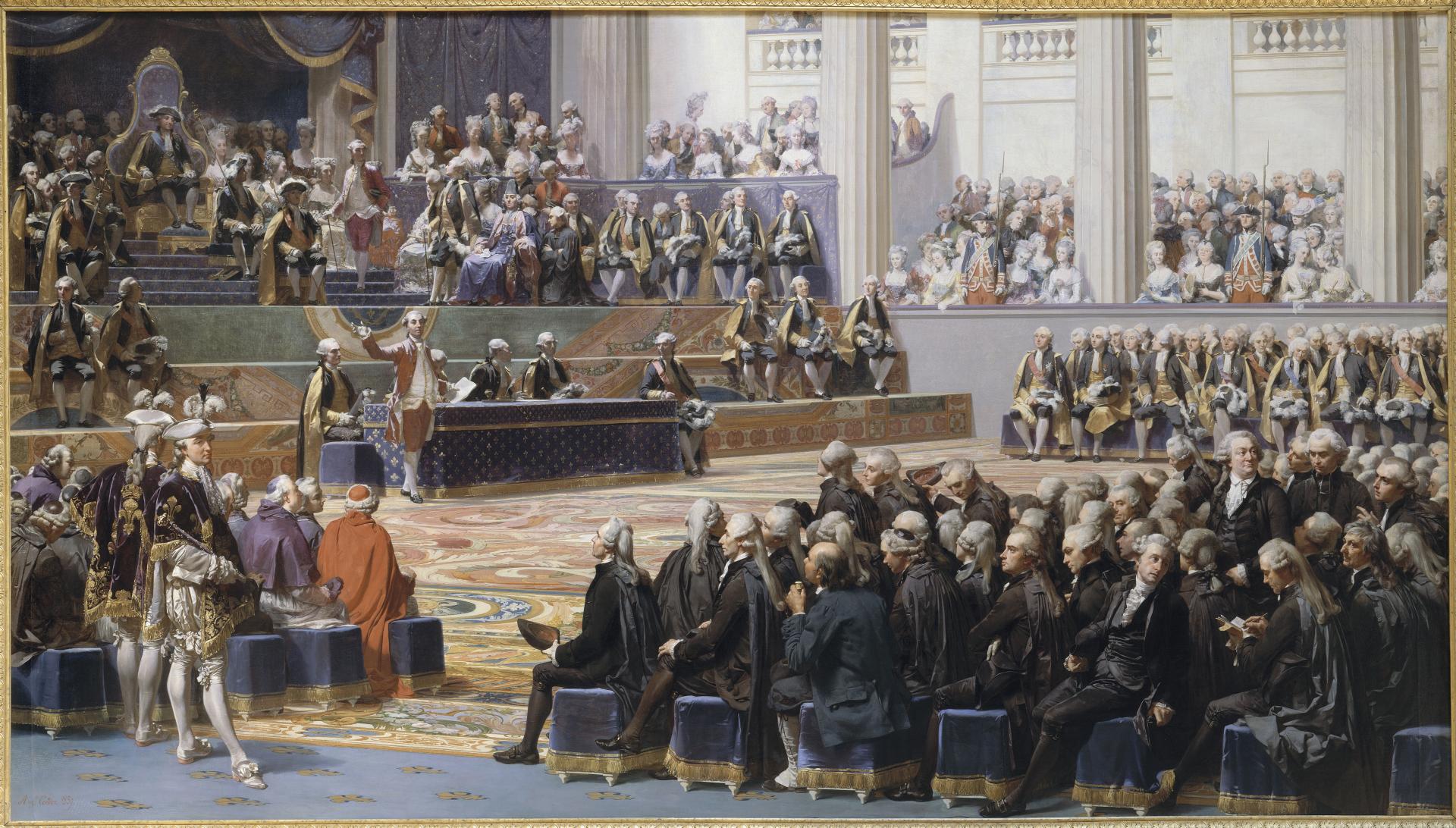

The representatives of each order – the Clergy, the Nobility and the Commoners – were invited to express their wishes and air their grievances. The first session was presided over by Louis XVI himself. He can be seen in the top left of this painting by Auguste Couder, sitting on his throne up on a podium, behind Necker, who has the floor.

Summoning of the Estates General at Versailles, 5 May 1789, by Auguste Couder

© RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles) / Daniel Arnaudet / Gérard Blot

The Estates General remained in session until 17 June 1789. Dissent quickly broke out among the deputies. The discussions were supposed to lead to a vote on how to reform the kingdom’s economy, but the deputies of the Clergy and the Nobility demanded that voting take place by order, thus guaranteeing them the majority. The deputies of the Third Estate, however, demanded one vote per head.

anecdote

The Estates General was a sort of council convened especially in times of crisis, and had not been summoned since 1614. The “statements of grievances” entrusted to the deputies present helped the king understand what his people wanted.

During the Estates General of 1789, Louis XVI took on the role of the peacemaker king. He declared himself to be “the people’s greatest friend”. But the deputies at the meeting were still not happy about what was being said by the king and his ministers, including Necker, who was more focused on financial issues that those to do with the vote. On 17 June 1789, the deputies of the Third Estate, together with some members of the Nobility and the Clergy, formed themselves into a “National Assembly”. Louis XVI immediately had the Menus-Plaisir shut down, whereupon the deputies relocated to a nearby venue: the Royal Tennis Court.

The tennis court oath

Having reconvened in the Royal Tennis Court, the deputies from the three orders took an oath vowing “not to separate and to meet wherever circumstances require, until the Constitution of the kingdom is established and grounded on solid foundations”. The Tennis Court Oath was taken on 20 June 1789.

As a united group, the deputies refused to bow to royal power.

anecdote

Various responses to this major event in French history are still remembered today, such as this one, by Deputy Bailly: “Go tell your master that the nation assembled takes orders from no one”; or this, by Deputy Mirabeau: “We are here at the will of the people, and will leave only at the point of a bayonet”.

Louis XVI had no choice but to concede. The self-elected “National Assembly” reconstituted itself as the “National Constituent Assembly” from 9 July 1789.

anecdote

The painter Jacques-Louis David planned to produce a huge painting of the taking of the Tennis Court Oath. In 1791, shortly after the event took place, David created an initial sketch. The plan was to depict the deputies in their finery and in action. However, political circumstances conspired against this grand project, which would forever remain in draft form only. A fragment of this unfinished canvas can be found in the attics of the Palace of Versailles…

The Tennis Court Oath, Jacques-Louis David

From the Bastille to Versailles

A few days later, on 15 July 1789, the storming of the Bastille, in Paris, caused a real panic at Versailles.

Storming of the Bastille, 14 July 1789

© RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles) / Gérard Blot

Senses were on high alert and the first courtiers started to abandon the Palace, including the counts and countesses of Artois, the king’s younger brother and sister-in-law, and also the Polignacs, for whom the greatest criticism was reserved. Gradually, the Palace of Versailles emptied of its occupants, even though the king himself seemed in no hurry to leave.

During the night of 4 August 1789, while the National Constituent Assembly was working on establishing the future constitution of the country, it voted to abolish feudal rights and privileges. This vote was one of the key moments of the French Revolution. At the same time, the National Constituent Assembly decreed that the future constitution would be preceded by a declaration of rights.

The abolition of privileges by the National Assembly

Thus, 26 August 1789 saw the signing of the Declaration of the rights of man and of the citizen – the founding document of the new political regime.

In this electrifying climate, a banquet hosted on 1 October, following a performance at the Royal Opera of Versailles, seemed like the last provocation by the monarchy and its representatives. The bodyguards had decided to organise a banquet to mark the arrival of the new Flanders regiment. A table was set for 210 on the Opera parterre, and the wine flowed freely. Toasts were raised to the royal family, who were hailed when they appeared. The orchestra launched into “Oh Richard, Oh my king” from the opera “Richard the Lionheart”.

These overt displays of loyalty to the monarchy sparked rage in Paris. The newspapers painted the banquet as an orgy and suggested that the tricolour cockade be trampled underfoot. Some were even said to have been flipped over to the white side – symbolising the king. Organising a banquet when the people were starving was too much for Marat, Danton and Desmoulins, who called for a march on Versailles.

The march on Versailles

On 5 October 1789, a procession of women, accompanied by a few men, met at Versailles. At this time, the king was hunting at Meudon, while Marie-Antoinette was walking on the Trianon estate.

News of the march spread quickly through the town, and the gates of the Palace were shut. The queen, having been alerted, returned to her apartments and the king returned to the Palace. He received a delegation of women, to whom he made many promises. The women were soon joined by representatives of the rioters, which compromised the safety of the royal family. In the Royal Courtyard, in front of the Palace, the crowd cried “To Paris! To Paris!” The reunited royal family left Versailles on 6 October 1789.

It is at this point that the Palace of Versailles ceased to be a royal residence.

The Palace after 1789

Between 1789 and 1804, the fate of the Palace remained uncertain. As he was leaving Versailles, Louis XVI still believed that the court might soon return. He even said to the Count of Gouvernet, who was remaining at Versailles in command of the National Guard: “You are in charge here – please try to save my poor Versailles.” But the Palace and the town quickly emptied of their occupants…