The founding act of French democracy took place at the very beginning of the Revolution, just a stone’s throw from the monarchic seat of power. On 20 June 1789, in the Real Tennis Room, not far from the Palace of Versailles, the deputies swore never to separate until they had given France a Constitution.

Jeu de Paume Oath, 1789 20 June 1789

The Oath of the Real Tennis Room: a founding act of French democracy

In the spring of 1789, Louis XVI summoned the Estates General to try and resolve the severe financial crisis that gripped his government and the nation. The assembly was constituted of the three Estates of the Realm: the Clergy, Nobility and Commoners. The deputies of the Commoners were expecting reforms, but they were soon disappointed, and refused to submit to the royal authority.

Refusing to sit according to their Estate, they solemnly established a National Assembly on 17 June 1789, along with a few members of the Clergy and the Nobility. The king tried to prevent the assembly by closing the Menus-Plaisirs hall in Versailles, where the deputies met, but, upon finding the door locked and guarded by soldiers on 20 June, the deputies withdrew to a nearby hall in which the sport of Real Tennis was played. It was here that they made the famous Oath of the Real Tennis Room:

“We swear never to separate and to meet wherever circumstances require until the kingdom’s Constitution is established and grounded on solid foundations.”

Anecdote

This event was a founding act of French democracy and a major contributing factor in the separation of authority and national sovereignty. It gave birth to the National Constituent Assembly, which in August 1789 voted for the abolition of feudalism and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

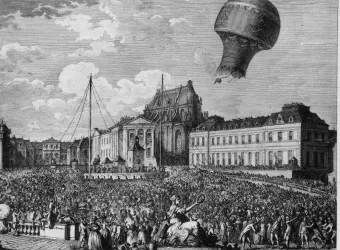

The Real Tennis Room: from a royal “sports hall” to a museum of the French Revolution

Built in 1686, this sports hall was privately owned. The royal family, and especially the king, played real tennis here, a type of ball game that was a predecessor of tennis. On 20 June 1789 the deputies of the Third Estate (the Commoners) made the famous Oath of the Real Tennis Room here, and on 7 'Brumaire'* of the year II (28 October 1793), a decree in the Convention procured the room for the French nation. It thereafter served a variety of purposes. (*Brumair was the second month in the French Republican Calendar, named after the French word 'brume', for the fogs common in that season, roughly October-November of our current calendar.)

In 1804 the room was used as a workshop by the painter Antoine-Jean Gros, as a military hospice in 1815, and as a workshop by the painter Horace Vernet during the reign of Louis-Philippe, before being fully restored under the Third Republic. The restoration work on the building and decor was undertaken by the architect Edmond Guillaume (1826-1894) and began in 1879.

Edmond Guillaume installed a Doric aedicule held up by two marble columns, which came from the Grove of the Domes in the gardens of Versailles. The aedicule was topped with a rooster in bronze sculpted by Auguste Cain and housed a marble statue of Jean Sylvain Bailly by René de Saint-Marceaux. Running around the edge of the room is a frieze of foliage in which the names of the signatories of the oath are painted. Twenty busts commissioned from contemporary sculptors represent the Assembly’s key members.

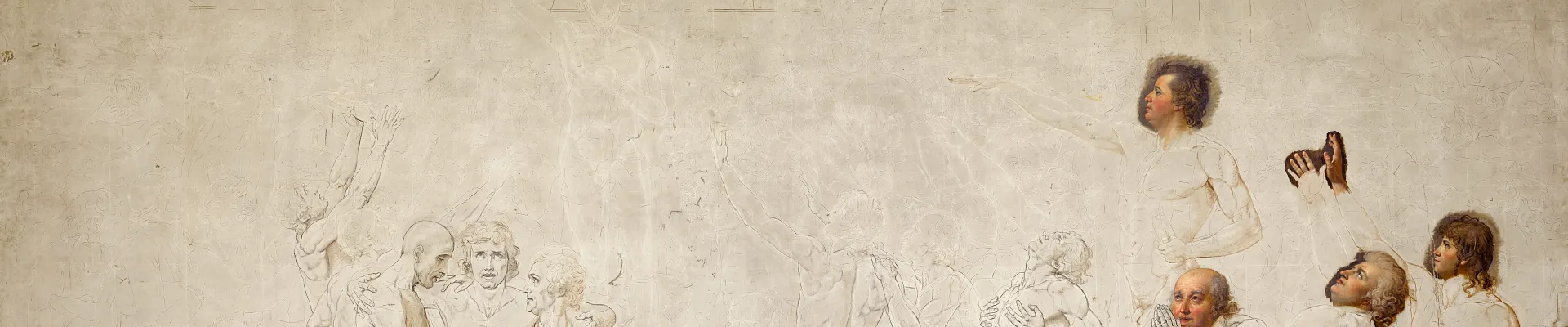

The monumental painting of the Oath of the Real Tennis Room

Inside the hall on the northern gable end wall is a painting by Luc-Olivier Merson from 1883, which reproduces the drawing of the Oath of the Real Tennis Room made in 1791 by Jacques-Louis David and which is now conserved in the Palace of Versailles. This monumental canvas was completed in just a few months by the artist and four assistants. It measures 10m by 6m and is an example of true technical prowess.

The Museum of the French Revolution was opened here on 20 June 1883.