After four years of devastating fighting, the First World War came to an end in 1919 in Versailles. The treaty, which represented “peace” for some and a “diktat” for others, also sowed the seeds of the Second World War, which would break out twenty years later.

The Treaty of Versailles, 1919 28 June 1919

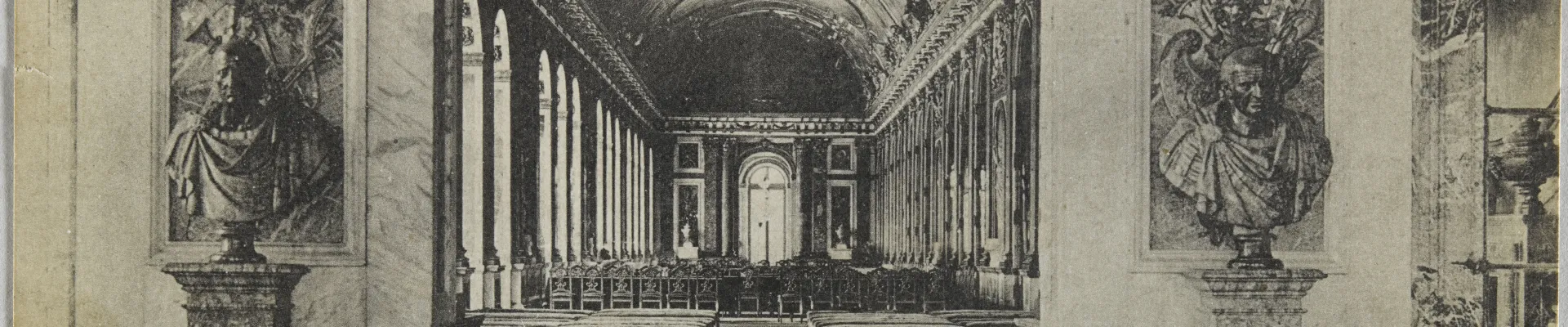

Almost half a century after the proclamation of the German Empire, Clémenceau, the Prime Minister of France, savoured his revenge on 28 June 1919, when the defeated German delegates signed the peace treaty in the Hall of Mirrors, in the same place where Germany had previously proclaimed its empire. The First World War was over. A Louis XV bureau had been placed in the centre of the hall beneath the emblematic painting of Louis XIV titled The King governs by himself. The session lasted 50 minutes. The solemn occasion, which was not celebrated with decorum or music, was attended by 27 delegations representing 32 powers. The four representatives of the principle allied powers were at the table: Clémenceau for France, Wilson for the USA, Lloyd George for Great Britain, and Orlando for Italy. The German delegation was composed of Müller, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and a jurist, one Doctor Bell.

Negotiations had proved difficult. The treaty had been drafted during a peace conference held in Paris starting on 18 January; but Germany had been shut out of the deal-making, while the Allies debated the matter alone, unable to agree amongst themselves: France wanted to definitively remove the German threat and cripple the country, Great Britain wanted to preserve its status, the USA dreamed of a peaceful world with the establishment of the League of Nations, and Italy wanted to take over the territories it had been promised in 1915. The treaty was eventually presented to Germany on 7 May. It was very harsh. The counter-proposals submitted on the 29th were all rejected. Germany refused to sign. On 17 June the Allies gave Germany five days to decide or have the war resume. Germany accepted the “diktat”.

It cannot be denied that the conditions were somewhat draconian. Germany accepted responsibility for the war and lost 68,000 km² of territory, including Alsace and Lorraine, which had been annexed in 1870, and 8 million inhabitants. Part of western Prussia was given to Poland, which gained access to the sea through the famous “Polish Corridor”, and Germany agreed to pay the crushing sum of 20 billion gold marks in reparations claimed by France. In addition, it lost most of its ore and agricultural production. Its colonies were confiscated, and its military strength was crippled. Humiliated, Germany seethed for revenge. A new war, which everyone had hoped to avoid, was already blowing up on the horizon almost as soon as the German delegation receded over it.